The Madrid Model

Note from Editor John Allen: This post started with a request from Madrid Ciclista in Madrid, Spain, to publish a translation of an article on this blog into Spanish. We were happy to comply. A look at their website revealed that Madrid has been thinking outside the box about bicycling. Miguel Cardo of Madrid Ciclista wrote the post below describing the “Modelo Madrid” in 99.44% perfect English.

Fire up Google Maps.

Switch to satellite view and have a look at any large avenue in my city, Madrid:

Lanes marked with that symbol have a speed limit of 30 km/h (about 19 mph). The default of 50 km/h (about 31 mph) is allowed in the other lanes. The marking with the oversized sharrow means:

- Bicyclists can use the lane;

- They have to ride in the middle of the lane.

All this started in 2013.

The city government was still reeling from the excesses of a real-estate bubble. Debt had ballooned to 7.4 billion euros after a failed Olympic bid. [1] The city could not even dream of any significant infrastructure project. A giant fine from the European Commission was looming for the city’s failure to reduce its pollution levels. [2]

City officials had to come up with something. This time they just couldn’t buy their way out of trouble. So they tried something different: a plan to increase cycling modal share without any large infrastructure projects.

The first plan was modest.

City officials started with a timid plan of “ciclocarriles 30” along the avenues and boulevards surrounding the Old Town. “Ciclocarriles 30” means 30 km/h bike lanes. The plan also included a municipal bike-share scheme that would use electric bikes, because Madrid is notoriously hilly. [3]

Municipal bike-share bicycle about to pass over a CC30 marking. Photo by permission of @MadCycleCuqui

In the beginning, nobody thought much of the plan.

In a chaotic and aggressive environment, motorists would not welcome the new users on “their” roads. Madrid city police have a well-deserved reputation for not enforcing traffic laws. Most people thought of the plan as some low-cost desperate measure to postpone the EU fine for a while, at least until a different administration was in charge. I’m not even sure that the city officials who created the plan had much faith in it.

Onward to Modelo Madrid.

Fast forward five or six years. Madrid city police still turned a blind eye to speeding, but the unexpected happened.

Fast forward five or six years. Madrid city police still turned a blind eye to speeding, but the unexpected happened.

Madrid’s undisciplined, chaotic, aggressive motorists can be seen moving slowly behind a cyclist, waiting for the right moment to overtake — changing lanes to pass in the lane to the left.

The true benefit of the 30 km/h (19 mph) speed limit is not that motorists comply with it, but that they drive at 15 km/h (9 mph) behind cyclists without even revving their engines. A new generation of cyclists — many of whom started riding on the new municipal white electric bikes — uses these roads with confidence.

Every road user is mandated to control his or her traffic lane.

A third measure sustaining this change was a city ordinance issued in 2010, which not only allowed but made mandatory riding on the center of the lane. [4]

In the video below, shot by the rider of a folding bicycle, nothing exciting happens, so don’t feel compelled to watch it all the way through.

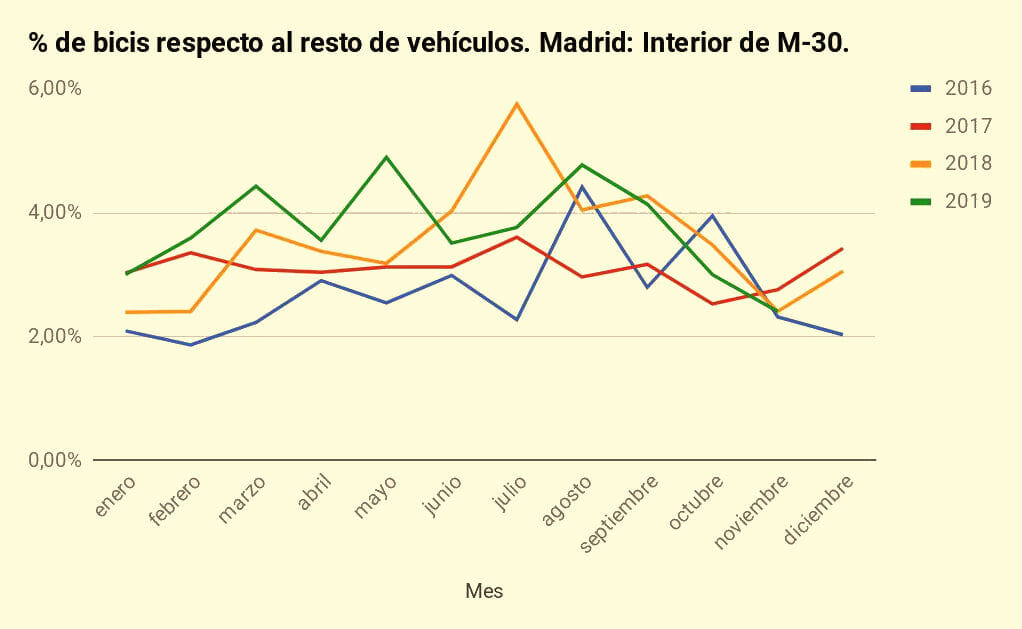

The number of cyclists is still modest (2-3 percent in the central area, according to counts by Madrid Ciclista) but growing. [5]

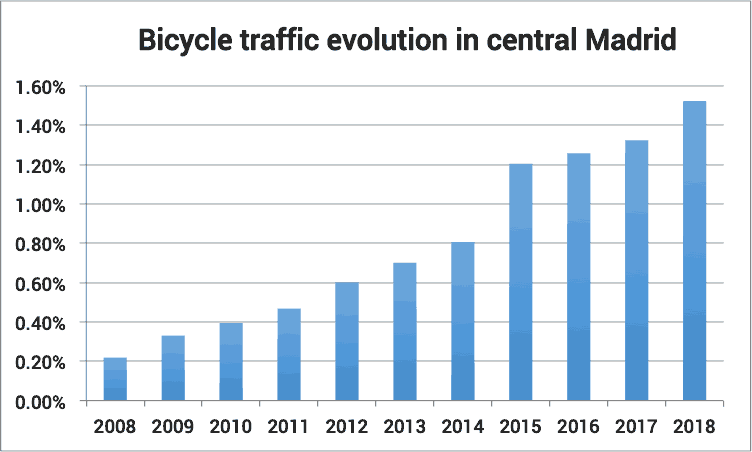

The graph below, from the city’s lower, less accurate counts, shows the trend from year to year:

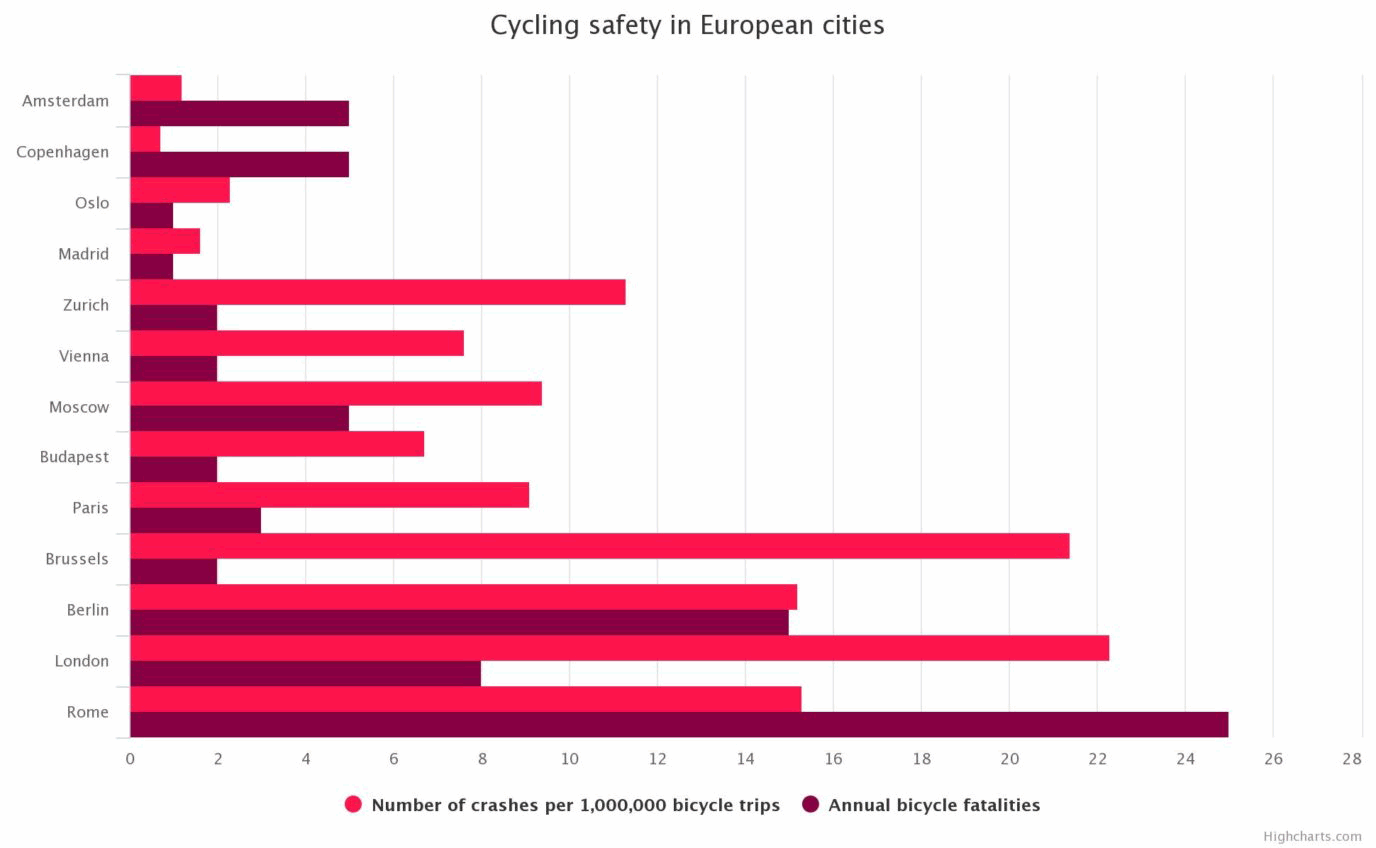

When compared with other European cities, the number of crashes per million trips is encouragingly low. [6].

We can now say that slow lanes were the origin of the so-called Modelo Madrid. The Madrid Model recognizes urban cycling as a transportation mode equal to any other, not requiring special infrastructure but granting the same rights to cyclists as to other vehicle operators. [7]

No cyclists ride on the sidewalk. Cyclists grant the same respect to pedestrians as they demand from motorists. Modelo Madrid puts in practice many of the principles pioneered by John Forester and refined in the United States by CyclingSavvy.

Modelo Madrid: the way of the future?

As with any other aspect of public policy, we can’t “ride” on our laurels — to paraphrase the English idiom — and expect equal treatment for cyclists in Madrid forever.

Economic stimulus money spent on “sustainable” projects is always a threat for urban cyclists, especially in these COVID-19 times. Going back to the segregated model is still possible. Some very loud cycling activists and associations are always demanding narrow bike lanes in the door zone or on sidewalks, following the North European model.

Here’s an example from Seville:

On the other hand, more Spanish cities are introducing slow lanes, especially after the COVID-19 lockdown: Valladolid, Burgos, Leganés, Granada…

Additional thoughts from Editor John Allen:

Which way should US states go? Could there be slow lanes on multi-lane streets in the USA? Keep in mind that higher speeds are common now on e-bikes, which probably did not in exist when Seville bikeways were planned and constructed.

Consider that automated crash avoidance is becoming common on motor vehicles, and improving. A transition to autonomous vehicles will follow, in time.

Suppose that a hoped-for decrease in motor traffic occurs with autonomous vehicles. Consider also the dangers of edge riding, and the reduction in efficiency and safety when turning vehicles must cross the path of through-traveling ones, rather than merging before turning.

All of these factors suggest that an integrated model like the Modelo Madrid could become more compelling as time passes.

Does US practice support the Modelo Madrid?

There is no specific mention in the model US traffic law [8] of different lanes with different posted speed limits. Yet these are in wide use, established indirectly.

In several states, large trucks are held to a lower speed limit than other vehicles [9], and are prohibited from using the leftmost lanes on multi-lane highways [10]. Edge-of-the road “friction” with parked vehicles, walk-outs, drive-outs and parking decreases the safe speed in the rightmost lane on city streets.

The general rule is to pass on the left, in the “fast lane”. But faster vehicles may pass bicyclists on the right in a right-turn lane, and sometimes a bus lane.

In all of these cases, the basic speed limit applies: to drive no faster than is reasonable and prudent. That speed is established by the design of the street and by the users who are present. Here’s an example of a bike lane to the left of a bus lane on University Avenue, Madison, Wisconsin. [11]

Footnotes

(Web links in the body of an article are more usual, but we prefer not to sidetrack readers into articles which need explanation, some in Spanish. So, these footnotes – Editor.)

[1] Newspaper article about the debt

[2] Newspaper article about the fine

[3] Online news article describing the original plan, with map

[4] City ordinance; translation of relevant sections into English

[5] Madrid Ciclista’s article “en Madrid no hay bicis” (“There are no bicycles in Madrid”) describes and promotes bicycle counts by citizens, and asserts that the city government has been undercounting.

[6] Crash rates in different European cities, and bicycle trends in Madrid. Article is in English: http://madridciclista.org/city-of-bikes/

[7] Madrid Ciclista article describing the Modelo Madrid.

[8] https://iamtraffic.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/UVC2000.pdf — see pages 147-148. Each US state enacts traffic law separately, and so there are differences.

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speed_limits_in_the_United_States

[10] https://static.tti.tamu.edu/tti.tamu.edu/documents/policy/congestion-mitigation/truck-lane-restrictions.pdf

[11] The University Avenue installation serves a large student population. The buses, on their fixed route, stay in the bus lane. More details here.

It’s quite remarkable to be reminded once again of how pernicious is the tyranny over the mind exercised by allegiance to a “conformist narrative”, no matter how well-intended such a narrative may be. Such narratives leave little room whatsoever for reasonable debate and discussion and oftentimes none whatsoever for any deviation from the “party line”.

How often we hear from bicycle “activists” of the need to “Copenhagenize” or “Amsterdamize” or “Bogotaize” :-) bicycling infrastructure in the United Sates. How much attention is given to the Colville-Andersens and the Peñalosas of the bicycle “advocacy” world!

But how little one hears of an alternative such as the “Madrid Model.”

Many thanks to the author and to the editors for bringing this important and apparently successful experiment in safe and successful urban bicycling to our attention.

It’s once again a pleasure to be reminded of how CyclingSavvy continues to think “outside the box.”

I think the argument to “Amsterdamize” has to do with % mode share. You will never get a significant % of the population to cycle if they feel threatened by cars, even if that threat is not real. Perception matters. It appears that the “Madrid Model” has been successful at capturing low hanging fruit but mode share stabilized at 2-4%. It is encouraging to see photos of women but how many 8 or 80 yr olds are using that system?

California has been using the “Madrid Model” for several years by painting sharrows and installing “Bikes May Use Full Lane” signs all over but it is not moving the mode share needle where I live. I read research that says sharrows improve safety by increasing passing distances but sharrows do not increase mode share. We need more than 2-4% bike mode share to save the planet.

My local Climate Action Plan targets 1.5% bike mode share by 2020 but I doubt we have achieved it and we live near a train station which dramatically increases cycling range. Our last status, from 2005, was 0.3% bike mode share.

Davis, CA was famous for decades for its high bike mode share but this was driven by making cars illegal on campus. Thousands of students cycle on normal width streets without any competition from cars. I knew students who used to transport their bikes to campus by car so they could ride on campus.

Amsterdam and Copenhagen are far more successful than any of our American cities for cycling mode share and safety.

The per capita safety numbers look encouraging but it might be because only the “brave and fearless” cyclists are taking advantage of the slow lanes since the article stated that ridership is still low. The “brave and fearless” are not bothered by competing for space with 3000 lb high speed crushing machines. How do we get the rest of the population out there?

Also, “brave and fearless” drivers tend to ride faster. What about the slower speeds of the young and elderly? From my experience in the “fast and furious” SF Bay Area, drivers are not patient with my 17-20mph but they get particularly peeved when my young daughters block their lane with 12mph or 6 mph uphill. For years, we rode up a very steep and narrow 1 block hill to get them to track practice and drivers routinely threatened us with their vehicles, sometimes very maliciously. We had people yell at us even from the opposite direction to get out of the way. My father cycled daily until he was 90 but he definitely slowed down with age. I do not think he would have fared well in the slow lanes of Madrid. When I take the lane, I always feel compelled to ride as fast as possible to mitigate my blockage of traffic. Sometimes I do not feel like riding full blast and would like the opportunity to relax by riding slower.

What about busy streets with only 1 lane in each direction? Taking the lane infuriates drivers, especially when there is little opportunity to pass due to heavy oncoming traffic. Our police think we are blocking traffic. This is a cultural issue with the drivers and police. What can we do to mitigate that?

Even with 30 years of cycle commuting experience in a number of countries and states, I often feel threatened while riding, especially when I take the lane. Consequently, I bought cameras to capture some of the egregiously dangerous driving behavior. I captured a number of attacks on my life because I had the audacity to take the lane. I have tried unsuccessfully to get the police to charge a couple of these incidents. Do you address road rage in your classes?

Yes, we address road rage as part of “Must Pass Bicyclist” syndrome. Mainly these are a set of strategies to attempt to put the kibosh on MPB/road rage before it happens in the first place.

It is stunning and scary what happens to some surely-otherwise-lovely people when they become motorists. In these pandemic times I’ve been pondering ways to form a better union.

As we move into the “new normal,” restoring cooperation among and courtesy toward all road users can’t merely be a pipe dream. Every single one of us deserves to feel safe and respected, no matter how we choose to transport ourselves.

Karen, what does the class teach about slower moving bicycles? The road rage is inversely proportional to bicycle speed, especially when the driver cannot pass due to oncoming traffic.

What about those single lanes with lots of oncoming traffic? One of our League trained Urban Cycling 101 instructors was truly dumbfounded when I took him on one of these roads. Taking the lane for the 3/4 mile segment wreaked havoc with backed up traffic, lots of honking and yelling even from oncoming traffic. We were travelling 12-14mph as it has a very slight up grade. He really did not know what to say after that experience. The drivers lost minutes rather than seconds so how do we convince drivers that is ok?

Does CyclingSavvy have any kind of educational program or out reach to drivers? The problem lies with the driver and not the cyclist. If we want cyclists to take the lane, we need to address the root of the problem, which is the driver.

cyclingsavvy, you bring up excellent questions that will take more than a few sentences for me to address. I’ll offer a couple of observations, though.

First: Bicyclist speed doesn’t matter. Even if you’re the fastest bicyclist on Earth, you are slower than any motorist…and NO motorist wants to be behind you. So how do we deal with this?

“Control and Release”- the CyclingSavvy technique for two-lane roads – is one of the most nuanced skills we teach. I probably rank among the worst marketers on Earth and prefer not to talk you into buying anything, but:

If you’re not already a Ride Awesome member on this site, 50 bucks will give you lifetime access to the seven-minute video that describes Control and Release (as well the entire online course content). If you want to jump to the Control and Release module, it’s the second video in the first topic of Mastery (the advanced course).

Ah, to have these ideas in every driver’s handbook! Especially crushing the myth that a solo bicyclist – or even two riding side-by-side – can cause significant delay to any motorist.

It’s simply too easy in the vast majority of cases to Change Lanes To Pass. EVERY motorist needs to know that.

Let’s do the math here. 1.76 miles at 12 mph is 50 seconds and at 30 mph — the highest speed limit likely on a street like the one you describe, it is 90 seconds. So, if the first motor vehicle behind you is right behind you as you enter the segment, you delay that vehicle by 40 seconds, assuming that nothing else delays it. That can be enough to annoy an impatient motorist. CyclingSavvy has strategies to avoid this, mostly by choosing when to enter. For example, waiting for the green rather than turning right on red will almost always result in no traffic behind you. Though I was an LCI, I encountered this strategy only when I took the cycling Savvy course.

Bruce,

As Karen writes below, cyclist’s speed matters very little when compared to normal motor vehicle speeds: it is always much slower. To drivers, passing a cyclist is similar to avoiding a double-parked car (something terribly common in Madrid): a short maneuver, quickly forgotten.

Busy streets with one lane in each direction are rare in Madrid, but I prefer riding on streets where drivers have it easier to overtake me. Anyway, it is a good chance to take notice of how far we have gone, when I see cars driving after me for a while and nobody honks or revs up.

Miguel,

Cyclist’s speed is only inconsequential if drivers have space to pass. I agree that bicycle speed is not important on multi-lane roads because drivers can always merge left to pass. However, cyclist’s speed is very important when passing is difficult. Drivers get very impatient when they cannot get around a double parked car due to oncoming traffic. The same is true for a bicycle and the frustration is inversely proportional to the speed of the bicycle.

Most of the roads in my area are 36′ curb to curb (2×10′ travel lanes + 2×8′ parking lanes). There is absolutely not enough space for a driver to pass with oncoming traffic. Traffic can be heavy since I live in a metro area so opportunities to pass can take some time. The SF Bay Area is famous for its hustle bustle fast pace and long commutes so drivers are not very understanding of delays.

There is a 1 mile problem stretch I commute on with my daughters from the time they were 7 yr old during the 5-6pm rush hour. If I block a driver for the whole way because they cannot pass due to a combination of oncoming traffic and poor visibility from a hill, I delay a 40mph driver by 3.5 min if I can only ride 12mph. It is a 1.75 min delay for half of the strip. Drivers get furious as cars stack up behind them.

You wrote: “When I take the lane, I always feel compelled to ride as fast as possible to mitigate my blockage of traffic. Sometimes I do not feel like riding full blast and would like the opportunity to relax by riding slower.”

See my 15 mph rides on what is believed to be one of the most dangerous streets in Los Angeles. No problem.

https://cyclingsavvy.org/2019/06/worst-city-to-ride-a-bike/

I have been working on defining a similar concept of a Personal Mobility Avenue with the diamond (special/restricted used) symbol accommodating Personal Mobility Vehicles (10< speed < 20) GVW under 750 pounds and non polluting.

https://1drv.ms/w/s!AvfYLfNGYLZ4g84wTtIshmXvBNTBmQ?e=qTa7Nz

My wife and I have been cycling for over three decades and have done month long bicycle tours across the USA and Western European countries. Our yearly mileage is over 7,000 miles a year. Regardless of the infrastructure afforded bicyclists by the various devices, there is one element to bicyclist safety on the roads that all the bicycle advocates over look. It is the attitude of motorists towards cyclist and cyclists towards motorists. In my experience, generally speaking, European motorists exhibit more respect towards cyclists than their USA counterparts. European motorists view bicycles as a vehicle with all the rights and responsibilities equal to an automobile. In the USA, motorists view bicycles as “toys” that should stay on the sidewalk. They will “tolerate” you on the road as long as you don’t inconvenience them. When I say “inconvenience” them I mean that you don’t cause them to lift off the gas pedal or turn the steering wheel. If you do, you’ll get a horn blown at you, an obscenity screamed at you, or they’ll buzz you and then give you the finger. We’ve even had things thrown at us simply for riding our bicycles on the road. USA bicyclists, conversely, generally speaking, operate their bicycles on the roads as if they are the center of the universe with no regard for the laws of the road under which they should be operating; i.e., stopping at stop signs or red lights, staying to the right of traffic so as not to impede the flow of traffic, etc. These mindsets, on the part of both motorists and bicyclists are the problem. Until you educate both motorists and bicyclist as to their rights and responsibilities with regard to operating their respective vehicles on the roads, these negative mindsets will persist, and you’ll never make bicycling on the roads any safer. Sad but true.

“Until you educate both motorists and bicyclists as to their rights and responsibilities with regard to operating their respective vehicles on the roads, …”

Amen, mcdermott5151. This is what we MUST do to ensure a civil and cooperative transportation culture. Truly we have no choice.

I shudder to think of existing within a world where behavior on our public roads is not civil and cooperative.

Regarding European attitudes toward cyclists, I think there’s a strong tendency toward rose colored glasses, viewing (almost) ever vacation as a “vacation in paradise.” My wife and I have bicycled in several European countries, and while most motorists were cooperative (with some memorable exceptions), I find most American motorists to be very cooperative too.

But more to the point, we’ve hosted touring bicyclists through Warm Showers for many years. An English gentleman who had toured multiple continents arrived at our Ohio home on his ride from the west coast. He assured us that American drivers were absolutely the most courteous of all.

Would this “Madrid Model” ever be accepted here in the U.S., as probably the most car-centric country in the world?

In reply to Mr. Krygowski, I erred in not specifically excluding excluding UK motorists in my favorable opinion of European drivers. I don’t include the UK when I discuss “Europeans”. The UK is not part of Europe. After having cycled in the UK for hundreds of miles in cities and backroads I concur that US drivers are probably on par with UK drivers in terms of their animosity towards cyclists. However, there is a huge difference in the attitude of “European” drivers compared to UK drivers with regard to sharing the road with cyclists. UK drivers have very little regard for cyclists. And by the way, my cycling in Europe has been for months at a time and at no time have I ever worn “rosy “ glasses. My cycling there has been self planned and self supported. Furthermore Mr. Krygowski, you are debating a topic with me based on your second hand knowledge. Hosting cyclists does not give you any hands on experience with riding a bike on a highway. Let me have your opinions on cycling in Europe after you have ridden over 5,000 miles there as I have.

I lived on the the outskirts of London for a couple of years (1999-2000), cycled in both the UK and Europe and I wholeheartedly concur with Mr. McDermott. The Belgians, Germans and Italians were all courteous but the French especially gave wide berth while the Brits played a game to see how close they can get before they hit someone, be it another car, pedestrian or cyclist. British roads are particularly narrow.

I was stunned at how close our real estate lady came to scraping the vertebrae of a person unloading their vehicle–super aggressive and would have paralyzed that person if she missed.

I remember nearly slapping mirrors with another driver but did not connect, so no noise. Still, this burly brute jumped out of his Mini to teach me a lesson. I did not hang around to learn.

I commuted to work a few times on extremely narrow back roads where I did not take the lane. Traffic was heavy/fast and drivers passed extremely closely. It was so incredibly stressful that I could never convince my wife to join me.

British drivers are much more skilled than American drivers due to more rigorous licensing requirements but they push themselves closer to the limits than American drivers in my experience. It seems like a 3′ American pass is equivalent to a 1′ British pass (since they have more control) but they both insist on passing at those minimum distances. I guess it is whatever your are comfortable with.

I was really surprised by the sentiment in the UK. In our very first conversation upon landing, our taxi driver from the airport conceded that they would rather be the 51st state of the US than part of Europe. I had no idea. He used the word “Europe” to describe an exotic, far off holiday destination just like we do.

Mr. McDermott, I’m simply saying that perceptions differ. My perceptions are based on tours or shorter rides (all self guided) in 11 European countries plus England, Scotland and Wales, plus many North American tours, including coast to coast. Plus decades of bike commuting, utility riding, recreation riding, club riding, etc.

I’m sure attitudes and locales differ. But the “American drivers are nicest” sentiment was by a man who had toured very extensively on at least four continents. (I don’t recall him specifically mentioning British drivers.) I can’t say whether he’s correct, but over my nearly five decades of avid cycling I’ve had very, very few really bad experiences. In my experience, incivility is rare.

As they say, YMMV.

I have no reason to disagree with your rating of driver courtesy in various European countries, but it correlates poorly with crash rates and numbers of fatalities as shown in a graph in the Madrid Model article.