Filtering Forward Past a Traffic Jam

Traffic congestion on urban streets is a fact of life, and no bicyclist wants to be stuck in it, breathing exhaust. Fortunately, a bicyclist can usually manage to avoid being stuck. If you ride in the same area for a long time, you develop a repertory of alternate routes. You might duck into an alley or take a shortcut through a park. You might use the sidewalk — with caution.

Many cyclists are unaware of the risks, or fatalistic, and take any option available. Savvy cyclists understand risks, avoid them and apply what might be described as a code of honor:

- Respect pedestrian rules in pedestrian space.

- Adhere as closely as possible to the rules of movement in driver space.

- Don’t make a motorist pass twice in a narrow lane if passing safely is difficult.

Filtering forward through a queue of traffic involves violating the rules of movement. Any time you violate the rules of movement, you increase your risk exposure. That doesn’t mean you should never do it, it just means you need to understand the risks and compensate for them.

Filtering Forward With Caution

Filtering forward in stopped traffic requires special caution, whether you are in a bike lane, shoulder or riding the edge of a shared lane. While it is legal in all cases, often the obligation to avoid a crash is on you. Passing on the right places you where others don’t expect you and often can’t see you. Sometimes you can’t see them either. So you need to expect them.

Filtering forward with no bike lane

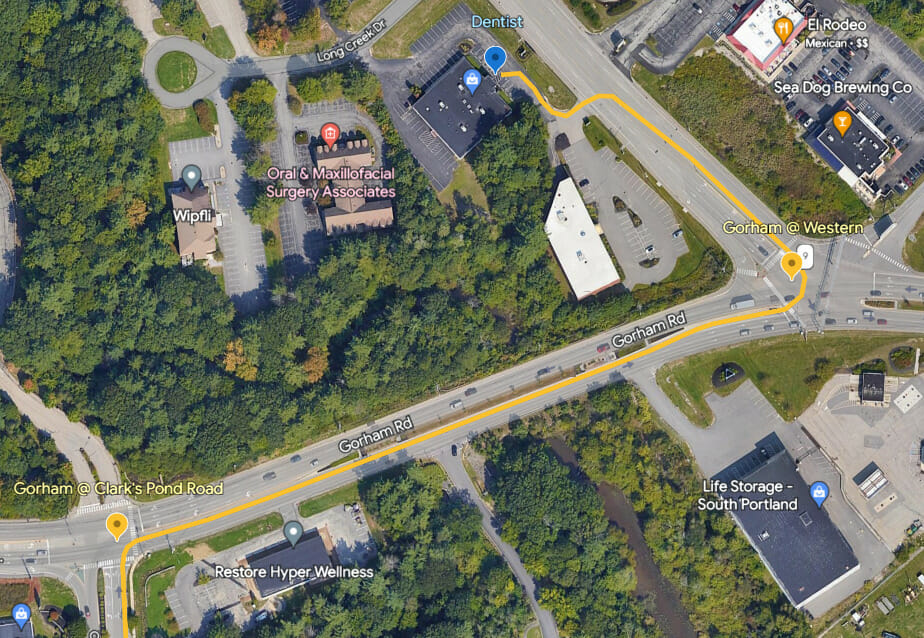

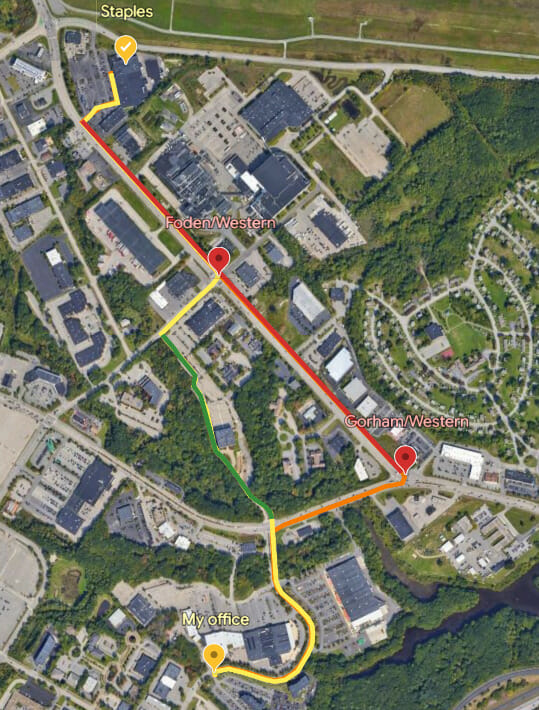

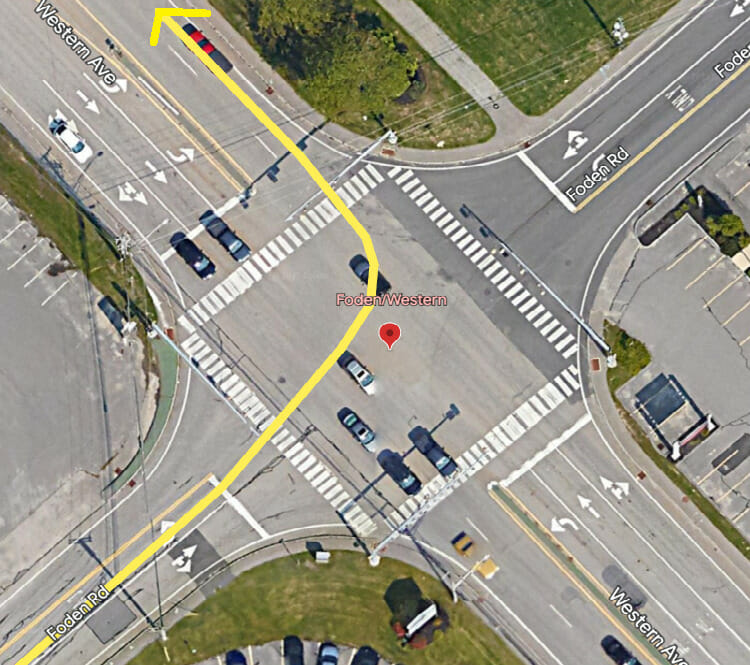

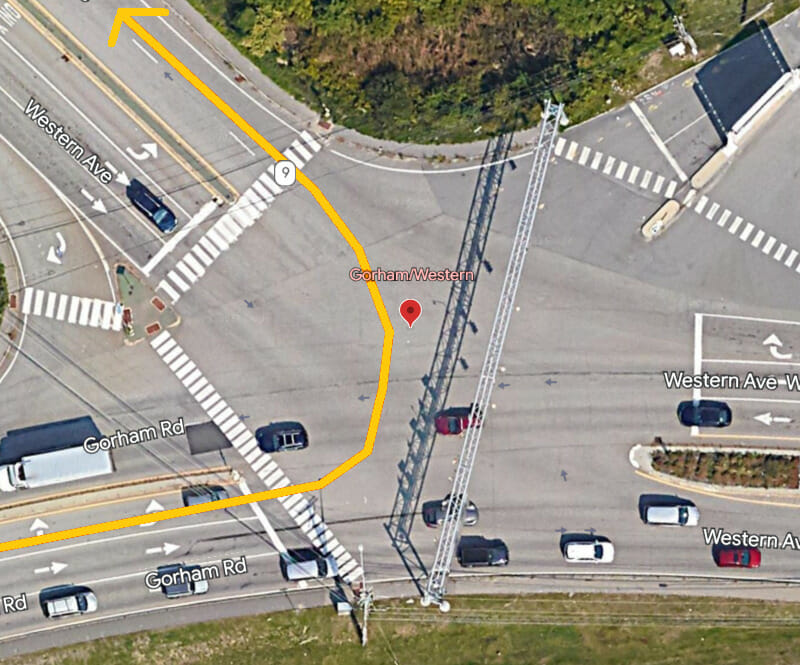

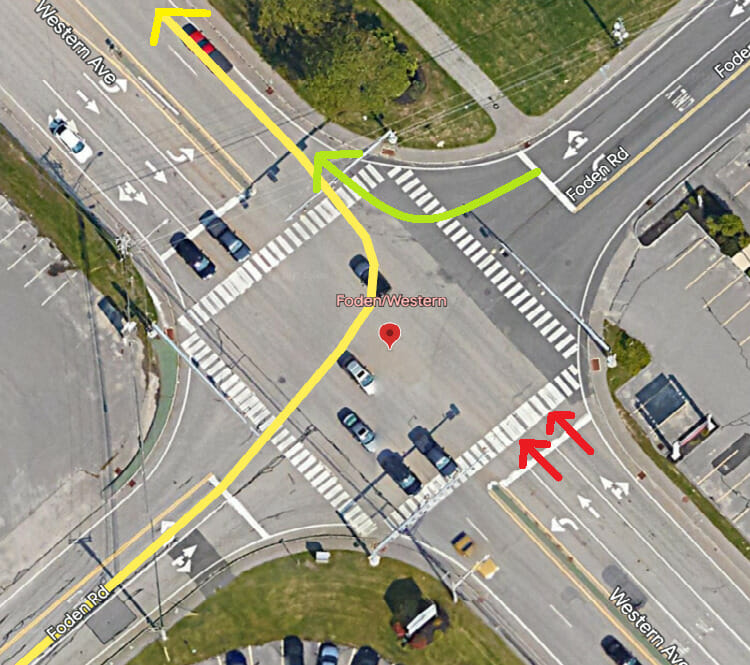

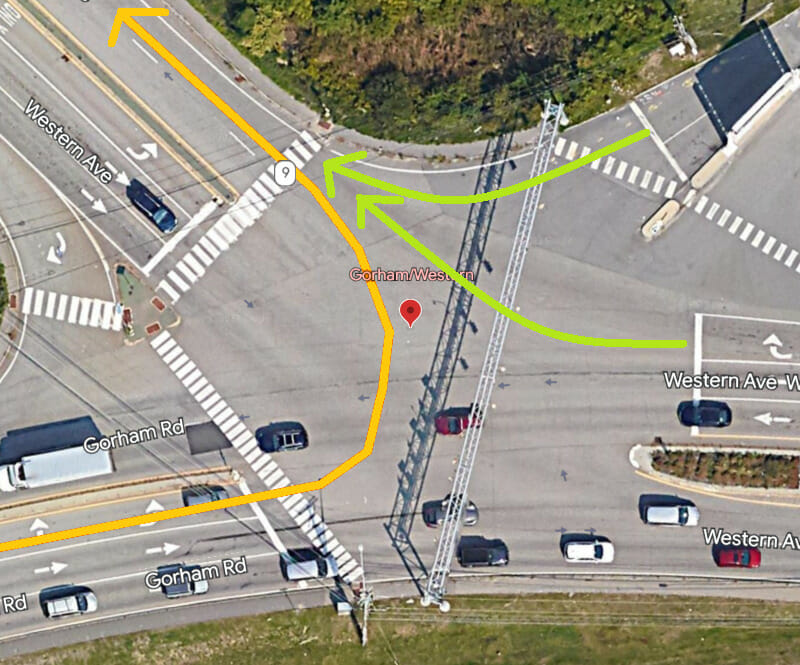

The video embedded above shows how I jumped the queue under highly challenging conditions. I was on a street with just enough room to pass stopped motor vehicles on the right (the location). There was no passing on the left, because the next lane carried opposite-direction traffic. I had to anticipate the many potential hazards. I moved forward cautiously and slowly only when I could avoid them.

What to watch for when filtering forward

Let’s recap what the video shows. Assume here that you are jumping the queue of stopped traffic on the right. (The same hazards are mirrored on the left side of a one-way street.)

The hazards include:

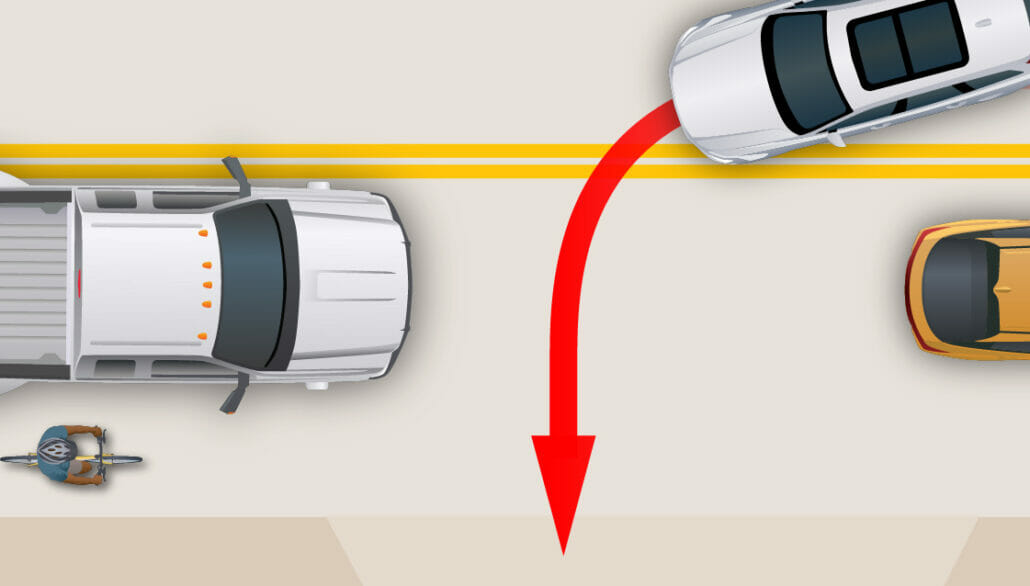

- Any vehicle moving forward, even very slowly, can merge or drift toward you. Pass only if the traffic is at a stop and you can tell that it is unable to restart.

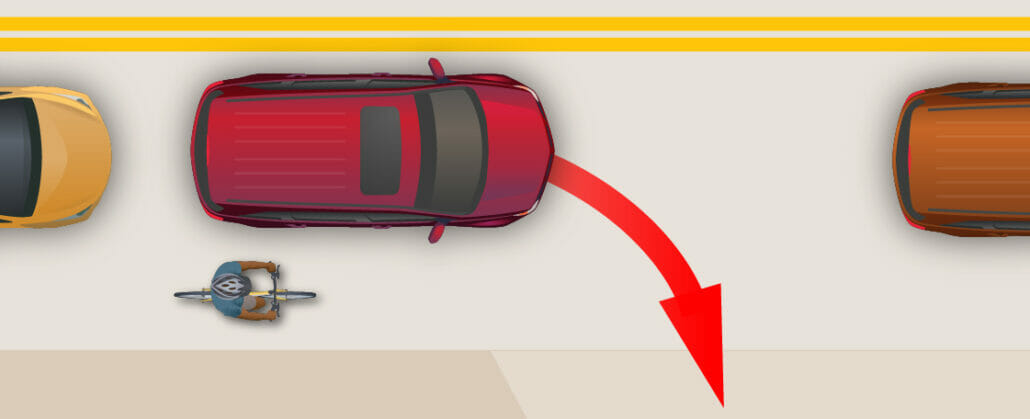

- A vehicle you are passing on the right can start up, turn right and right-hook you at any entry to a street or driveway. And so my rule is never to pass a vehicle on the right if there is a street or driveway ahead into which it might turn.

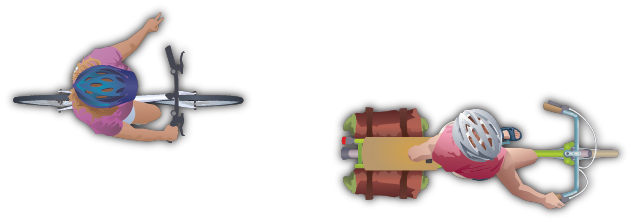

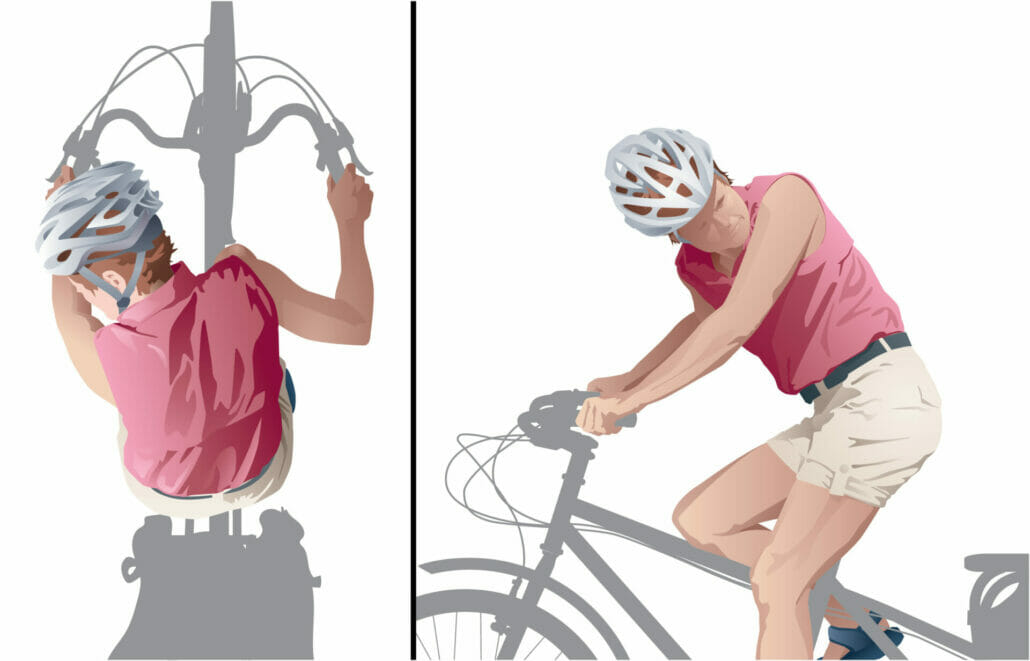

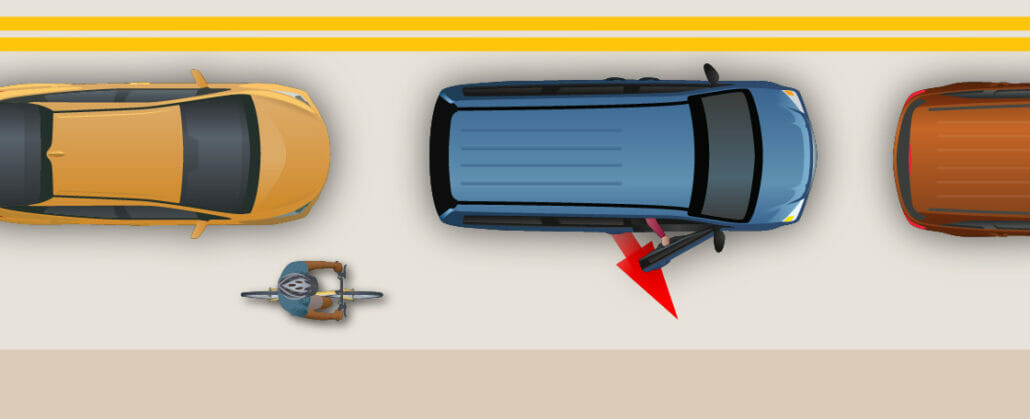

- Doorings and walk-outs can happen as usual from the curb side, but also from the street side — most common with taxis and other ride-share vehicles, but it can happen with any vehicle.

- Never pass a bus or large truck on the right. It may start to turn or merge while you are passing, trapping you. Off-tracking can sweep you underneath. Buses and trucks often have signs, “if you can’t see my mirrors, I can’t see you.” That does not mean “if you can see my mirrors, I saw you.”

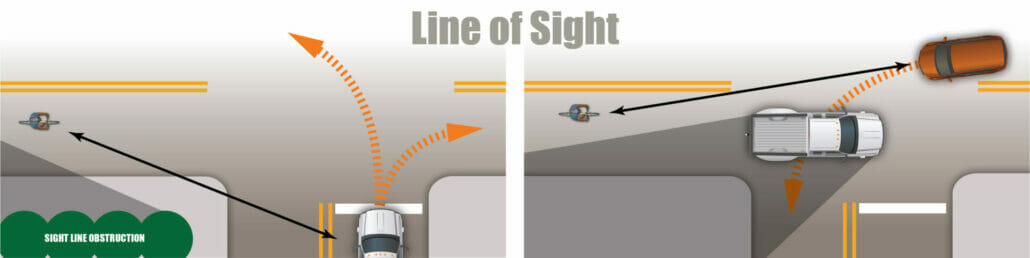

- Vehicles you are passing hide you from cross traffic — motor vehicles, bicycles, pedestrians. You avoid the risk by slowly and cautiously approaching the front of a vehicle when there is a gap ahead of it, and looking before you proceed. A pedestrian needs only the narrow gap which every driver leaves in a queue.

Avoiding Passing Problems

Other bicyclists, and other riders of narrow vehicles, may not be as cautious as you are. They may buzz-pass you on either side, or hook you. You need to keep a straight line, and check for overtaking traffic even in a narrow space.

Tactics for avoiding hazards:

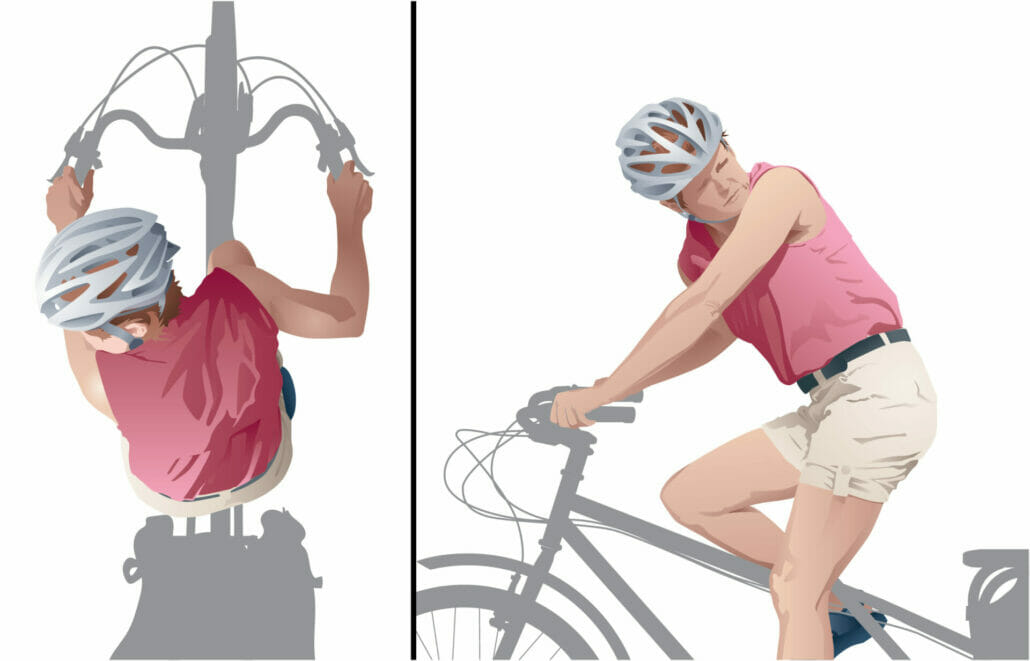

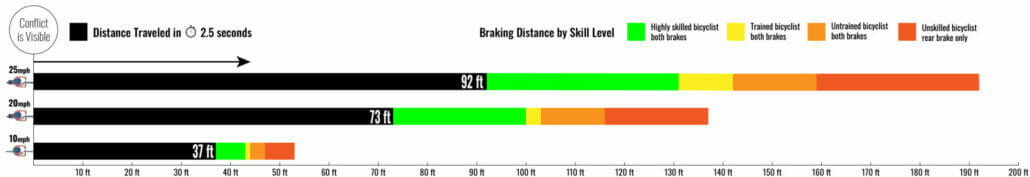

- Keep your speed slow enough that you can scan thoroughly and stop instantly. Keep your hands on the brake levers.

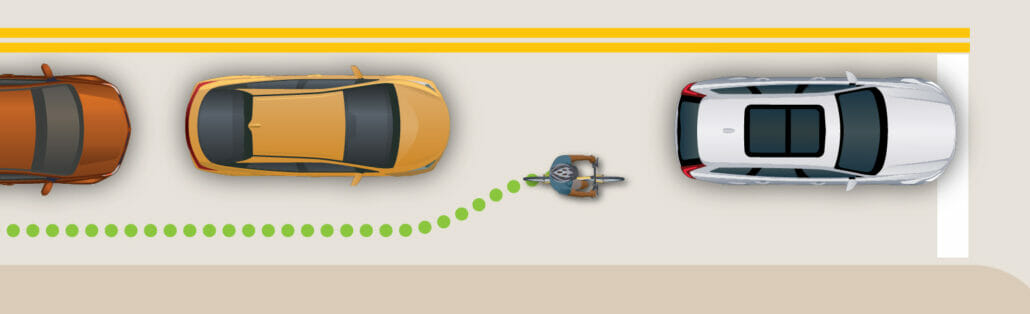

- Stop in the gap between vehicles, where the vehicle ahead of you poses no threat and the driver in the next one can see you.

- To change lanes to position yourself correctly for your destination, negotiate with the driver of the vehicle you have just passed. In these close quarters, you can actually establish face-to-face communication.

- Don’t pass the first vehicle waiting at an intersection. You can’t know which way it will turn: people forget to use turn signals, or change their minds about which way to go. You might also check whether the front wheel is turned toward you.

- As traffic starts moving, signal to the driver behind you and move into high-vantage position (where you can see past the left side of the vehicle ahead of you). As traffic gets moving faster, you may release lane control as appropriate.

- To the extent possible, be visible and communicate.

- Honor first come, first served. Before you pass a queue in a narrow lane, consider whether the traffic will be moving fast again after the light and how difficult it will be for those same drivers to pass you (again… because they may have passed you once already).

- Enter an intersection only if you can get through it.

Yes, it’s slow, but…

Complicated and slow? Yes, but even at 5 or 6 mph, you are going faster than the drivers stuck in their traffic jam.

First come, first served conundrum

What if you’re on a 2-lane road and come to the end of a long queue at a red light? You know you will not make the green light if you stay in the queue.

You might even sit through more than one cycle. Even worse, the light could change and the line of cars could pull away from you. And then you are the reason the ones behind don’t make the green light.

It makes sense to filter forward. But then what if you’re in front of everyone and the light changes, and now they can’t pass you easily?

What now? One strategy is to go through on the green, then pull over and wait for the platoon to pass. The light will change eventually, shutting down the traffic and allowing you to move forward on a nearly empty road for a while. Often, this could be as much time as you need to get to a wider stretch or your next turn.

Congested two-lane roads present the most challenging and unpleasant environment for bicyclists. Multi-lane roads seem more intimidating, but are less stressful.

Lead us not into temptation

People like to get ahead. Many bicyclists find it tempting to break rules to get somewhere faster.

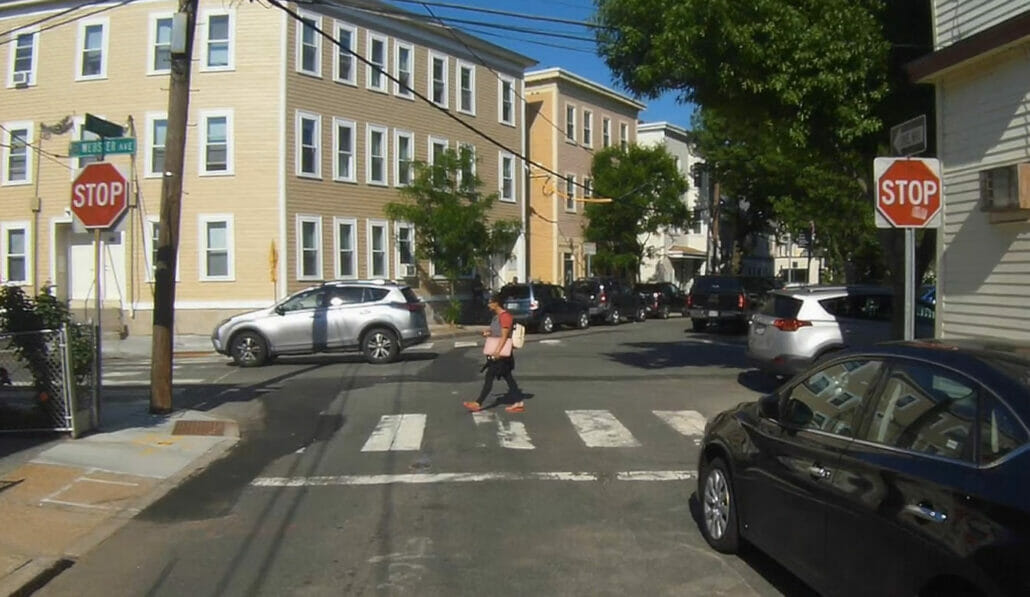

Congested traffic increases temptation, because of the need to slow and stop repeatedly.

Sometimes strategies can actually increase delay. For example, while the sidewalk might seem faster, pedestrians are always shortchanged by signal timing at intersections. Riding as a bicycle driver, I have often passed bicyclists who attempted to get ahead on the sidewalk, but got stuck. The cyclist whizzes past me on the sidewalk while I am stopped in the queue. Then the traffic starts moving and I pass that bicyclist, who is waiting to cross in a crosswalk. While it’s tempting to violate a red light or “don’t walk” signal, you assume the liability if someone hits you while doing that.

Beware of manufactured temptations

A number of measures intended to make bicycling more attractive or safer can create a false sense of security, or make it easier to take risks, or both.

Bike lane…

A striped bike lane makes it much easier to pass on the right. The wider channel to the right of stopped traffic invites bicyclists to filter forward, and at higher speeds. But, contrary to popular belief, bike lanes do not increase motorist caution or awareness. A bike lane does not give you x-ray vision to see through stopped and parked vehicles, or clairvoyance to anticipate conflicts. The same cautions apply with or without a bike lane. Since I shot the video above, bike lanes have been striped at the location. They increase mobility, but not safety, when motor traffic is at a stop.

Bike box…

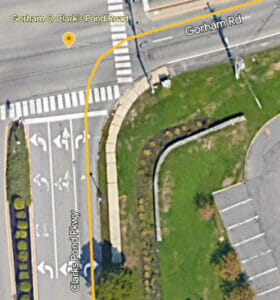

A bike box— also also called bicycle waiting area — invites bicyclists to filter forward in a bike lane, and then wait ahead of the queue. It takes the concept of jumping the queue to a higher level, lending official support to bicyclists’ getting ahead of the line.

Sounds great, right?

Do you know when the light is going to change? Right on red is prohibited where there is a bike box…Everyone must turn right on green. If you arrive just after the light has turned red and the first vehicle has stopped, it’s safe to move into the box in front of it. But what if the light has been red for a while? It could turn green just as you get there. It’s not just a risk to move in front of cars that are about to move, some of those cars may be waiting to turn right. Arriving at the intersection just as the light turns green puts you at risk of being right hooked, or cut off by a line of right-turning cars. Slipping into the queue before you reach the intersection can keep you clear of this risk.

Barrier separation…

A barrier-separated bikeway does not remove crossing and turning conflicts, and can make them worse if the barrier is opaque — vegetation or a wall of parked cars. It presents the same crash risks as when riding on a sidewalk. Oh, and while safety is increased by separate signal phases at intersections, so is delay. Always, always, the “cars” will get the lion’s share of the green time.

Rely on yourself, no one else is looking out for you

Several measures attempt to make motorists more attentive to bicyclists. These measures include green paint in the bike lane, a “yield to bicyclists” sign, a “watch for bicyclists” sticker for a driver’s side mirror. All of these measures depend on the motorist’s remembering to look… which relies on their paying attention and being present. Good luck with that.

Summary

Many of us are proponents of the principle of same roads, same rules, same rights. As with any ideology, it’s senseless to take this to the extreme. This is one more reminder that the biggest cause of significant delay in the road system is cars. Traffic congestion adds hours to car trips. One of the advantages of driving a narrow vehicle is that you can slip past all that delay. While filtering forward is risky, you can avoid trouble by understanding the risk areas and being mindful and cautious.