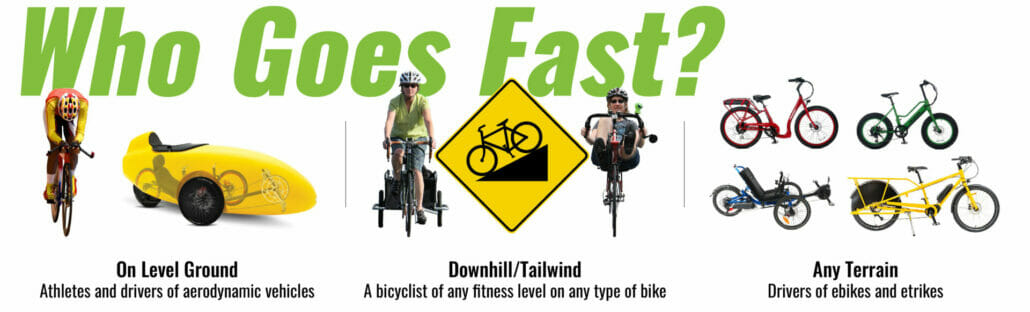

Nobody expects a bicyclist to go uphill at 20mph

Motorists don’t always have the best judgment about how much clear distance they need to pass a bicyclist. If anything, they expect to be able to pass in a very short distance, especially on a hill. Nobody expects a bicyclist to ride uphill at 20mph. Yet ebike riders can do that easily!

In this video let’s look at how much extra distance is required to make a safe pass, and how an ebike rider takes charge to balance courtesy and safety.

Control & Release is one of our signature strategies for finding the balance between controlling travel lanes for protection and facilitating passes when it is safe and appropriate.

We release because we control.

Many bicyclists ride as close to the edge as possible on narrow roads.

If you’re reading this, you probably already know the problems with that. Sometimes it’s safe and makes sense to move momentarily to the edge in order to facilitate a pass.

But riding there by default subjects a bicyclist to edge hazards. The faster you ride, the faster the edge hazards come toward you.

Riding on the edge also subjects you to high-speed passing that can be too close, as well as motorists passing into oncoming traffic and then swerving back into you. You’re leaving your safety in the hands of strangers. When you keep usable pavement to your right, you have someplace to go if someone gets too close.

The gift of lane control.

Even better, when you ride farther left, you have a way to positively communicate your cooperation with overtaking motorists. Sonoma County Bicycle Coalition’s David Levinger described this beautifully:

“I believe in gift-giving as a way of relationship-building. If I don’t ride farther to the left, then I don’t have anything to give.”

“I believe in gift-giving as a way of relationship-building. If I don’t ride further to the left, then I don’t have anything to give.

“But if I ride further to the left, and I wave, and I move to the right, then I’m giving a gift to this person.

“If I were riding on the right stripe, I would just be an a__hole.”

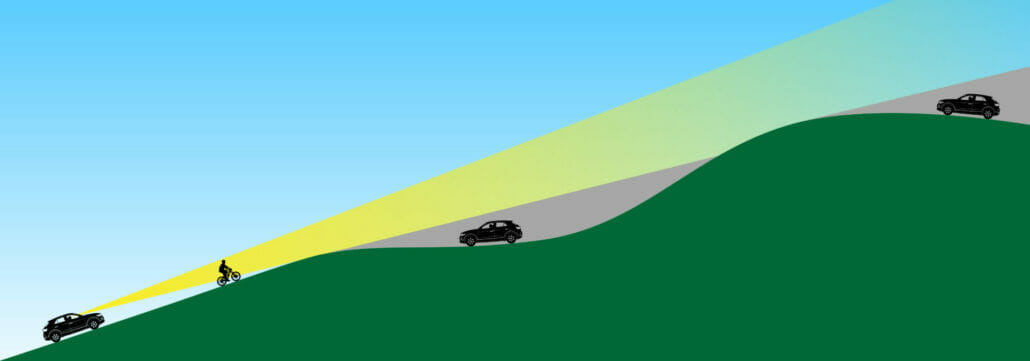

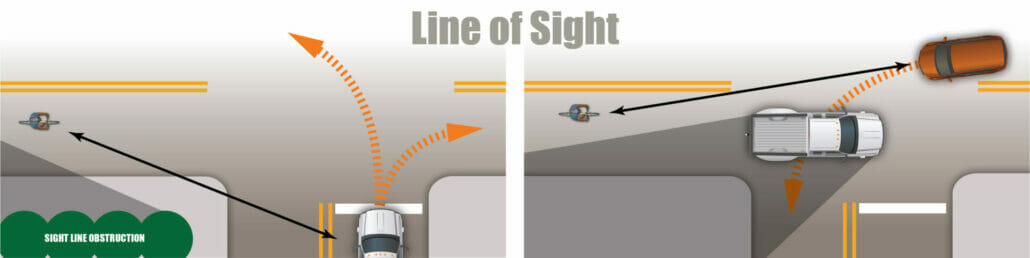

Hills hide hazards.

We control because we recognize the likelihood of unseen hazards ahead. The video below shows a hill so steep you can’t see oncoming vehicles until you reach the crest. The last 200 feet are more than a 12% grade. Even with pedal assist, I was working to maintain 15mph in the steepest part. My car struggles on this hill!

On a previous ride up this hill, I did not take an assertive enough stance and a motorist passed me within 100 feet of the crest. A car came over the top as the passer was beside me.

Luckily, I had a driveway to duck into. I won’t leave it up to a motorist to make the right decision again.

It’s not just the top of a hill that hides oncoming vehicles. A dip or flat spot can also obscure potential hazards from the line of sight.

This can be especially deceiving if the road above the dip is empty. That scenario appears in the video at the top of this post.

You’re not only protecting yourself.

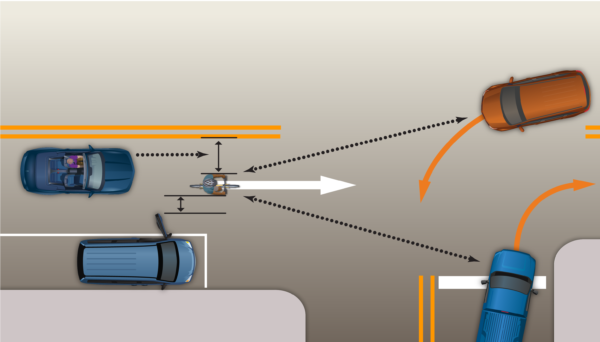

The most common hazard for an overtaking driver is an oncoming vehicle. A bad pass puts both motorists at risk of a head-on collision. There could also be an oncoming bicyclist.

One time I crested a hill and saw a woman pushing a stroller in the oncoming lane. I was holding back a truck from passing at the time.

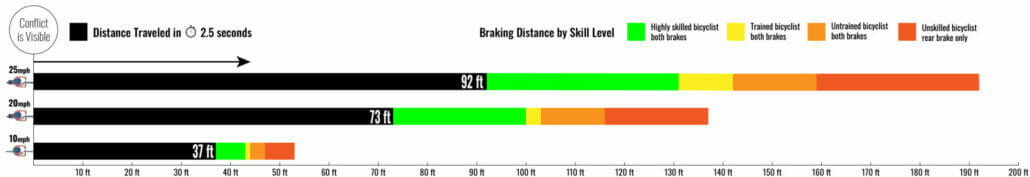

More time and distance are required to pass a faster bicyclist.

The graph below is simplified to show how much longer an overtaking vehicle would need to be in the oncoming lane based on a Class 1 or 2 ebike speed, vs. a typical speed for a bicyclist climbing an 8-10 percent grade.

Motorists expect bicyclists to be slow.

A slow bicyclist can be passed with minimal time in the oncoming lane. Even so, a legal pass should allow for additional sight distance. No bicyclist should be passed near the crest of a hill.

An ebike rider at maximum assist or full throttle will be much farther down the hill when it becomes unsafe to initiate a pass.

An approaching motorist is unlikely to assess the speed of a bicyclist ahead. It will simply register as a bike—a thing to be passed.

This is why ebike riders need to be proactive with more control and communication.

The culture of speed could use some remediation.

It’s also why we need to be training motor vehicle drivers to fully assess the situation before passing a bicyclist. The notion that bicyclists are always slow was never true, but it is even less so now. And you know, the whole car-centric culture of speed could use some remediation, too.

There are a few essential tools for

Control & Release

Communication is our most powerful tool.

Bicyclists communicate with lane position and hand signals. Lane position does most of the work for sensible motorists.

Passive Control. This is the default position, between the right tire track and the center of the lane. It communicates to a motorist that he cannot pass at will within the same lane and will need to use part of the oncoming lane to pass.

Passive Discouragement. Moving closer to the lane line discourages a motorist from initiating a pass.

Active Discouragement. Maintaining that left-side position and adding a hand signal does two things: It confirms you do not want the motorist to pass, and it acknowledges that you knows he is back there. This is both instructive and humanizing.

Passive Release. Moving to the right (not the edge) sends an intuitive message that you are releasing the lane. You can also stop pedaling, which is both communication, and a way to slow and decrease the distance needed to pass.

Active Encouragement. This isn’t always necessary or appropriate, but if it is clear ahead and that clear distance is time-sensitive, a little come-around signal communicates intent to cooperate and can reduce hesitation.

Reward. Share some love! A friendly wave will thank the motorist who safely passed you. It feels good to be thanked, even if they’re being thanked for something they are required to do (pass safely).

Learn more about communication in the Mastery Course.

When control fails. If an emphatic hand signal and assertive lane position fail to stop an impetuous motorist, your best move is to reduce speed rapidly and move to the right. If a car comes out of the blind spot, you need to be out of the way.

A mirror is useful.

Over the decades, I have ridden many miles with and without a mirror.

I find a mirror to be essential equipment on 2-lane roads. It lets me know when a vehicle is approaching at a distance. I can look ahead and determine what the sight lines call for. I could move to the right and slow so the motorist can pass well ahead of a blind hill or curve. Or I might hold my position and signal the motorist to stay back until there is enough sight distance, or a place for me to move aside (like a clear shoulder).

I used a mirror but did not rely on it as much when I rode in an urban environment. Now that 90 percent of my travel is on narrow rural roads, I would not want to be without it.

This is a dance you lead.

It’s an epiphany to realize that we bicyclists have control of our environment. Our control comes from communicating and being predictable.

There are certainly easier places to ride than on rural two-lane roads. But if these roads are where you ride, then Control & Release is the dance you get to lead.

About the camera rig.

The camera is a Garmin VIRB 360 (out of production), a single camera that shoots in all directions. There is a downside to that: the resolution of cropped views is marginal.

To include the bicyclist in the front frame, the camera is mounted on a painter’s pole with a screw-on camera mount. I used musician’s drum clamps and foam pipe insulation to mount the pole to the bike frame.

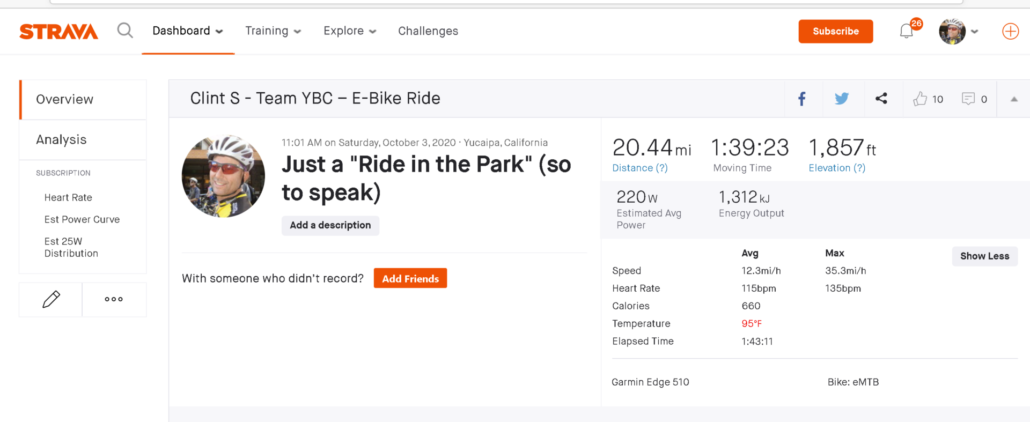

The ride is a Pedego Boomerang Class 2 ebike with torque-sensing hub drive.

Shannon learned to ride when she was 11, but for the next 30 years or so, showed no interest in bicycling, except to comment on observations she’d made from behind the wheel of her car.

Shannon learned to ride when she was 11, but for the next 30 years or so, showed no interest in bicycling, except to comment on observations she’d made from behind the wheel of her car.