The Madrid Model

Note from Editor John Allen: This post started with a request from Madrid Ciclista in Madrid, Spain, to publish a translation of an article on this blog into Spanish. We were happy to comply. A look at their website revealed that Madrid has been thinking outside the box about bicycling. Miguel Cardo of Madrid Ciclista wrote the post below describing the “Modelo Madrid” in 99.44% perfect English.

Fire up Google Maps.

Switch to satellite view and have a look at any large avenue in my city, Madrid:

Lanes marked with that symbol have a speed limit of 30 km/h (about 19 mph). The default of 50 km/h (about 31 mph) is allowed in the other lanes. The marking with the oversized sharrow means:

- Bicyclists can use the lane;

- They have to ride in the middle of the lane.

All this started in 2013.

The city government was still reeling from the excesses of a real-estate bubble. Debt had ballooned to 7.4 billion euros after a failed Olympic bid. [1] The city could not even dream of any significant infrastructure project. A giant fine from the European Commission was looming for the city’s failure to reduce its pollution levels. [2]

City officials had to come up with something. This time they just couldn’t buy their way out of trouble. So they tried something different: a plan to increase cycling modal share without any large infrastructure projects.

The first plan was modest.

City officials started with a timid plan of “ciclocarriles 30” along the avenues and boulevards surrounding the Old Town. “Ciclocarriles 30” means 30 km/h bike lanes. The plan also included a municipal bike-share scheme that would use electric bikes, because Madrid is notoriously hilly. [3]

Municipal bike-share bicycle about to pass over a CC30 marking. Photo by permission of @MadCycleCuqui

In the beginning, nobody thought much of the plan.

In a chaotic and aggressive environment, motorists would not welcome the new users on “their” roads. Madrid city police have a well-deserved reputation for not enforcing traffic laws. Most people thought of the plan as some low-cost desperate measure to postpone the EU fine for a while, at least until a different administration was in charge. I’m not even sure that the city officials who created the plan had much faith in it.

Onward to Modelo Madrid.

Fast forward five or six years. Madrid city police still turned a blind eye to speeding, but the unexpected happened.

Fast forward five or six years. Madrid city police still turned a blind eye to speeding, but the unexpected happened.

Madrid’s undisciplined, chaotic, aggressive motorists can be seen moving slowly behind a cyclist, waiting for the right moment to overtake — changing lanes to pass in the lane to the left.

The true benefit of the 30 km/h (19 mph) speed limit is not that motorists comply with it, but that they drive at 15 km/h (9 mph) behind cyclists without even revving their engines. A new generation of cyclists — many of whom started riding on the new municipal white electric bikes — uses these roads with confidence.

Every road user is mandated to control his or her traffic lane.

A third measure sustaining this change was a city ordinance issued in 2010, which not only allowed but made mandatory riding on the center of the lane. [4]

In the video below, shot by the rider of a folding bicycle, nothing exciting happens, so don’t feel compelled to watch it all the way through.

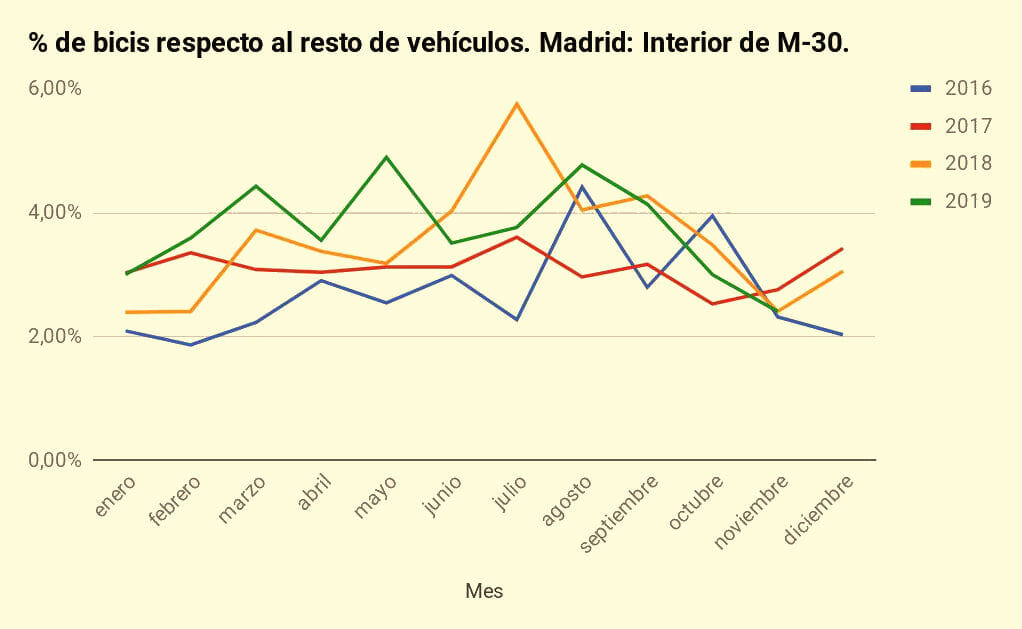

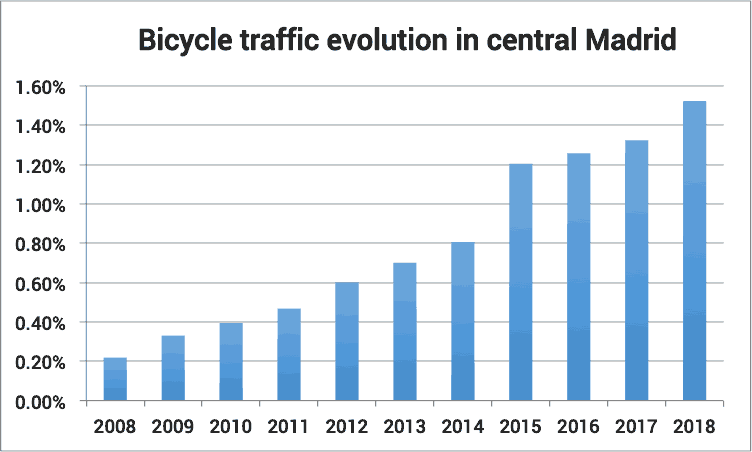

The number of cyclists is still modest (2-3 percent in the central area, according to counts by Madrid Ciclista) but growing. [5]

The graph below, from the city’s lower, less accurate counts, shows the trend from year to year:

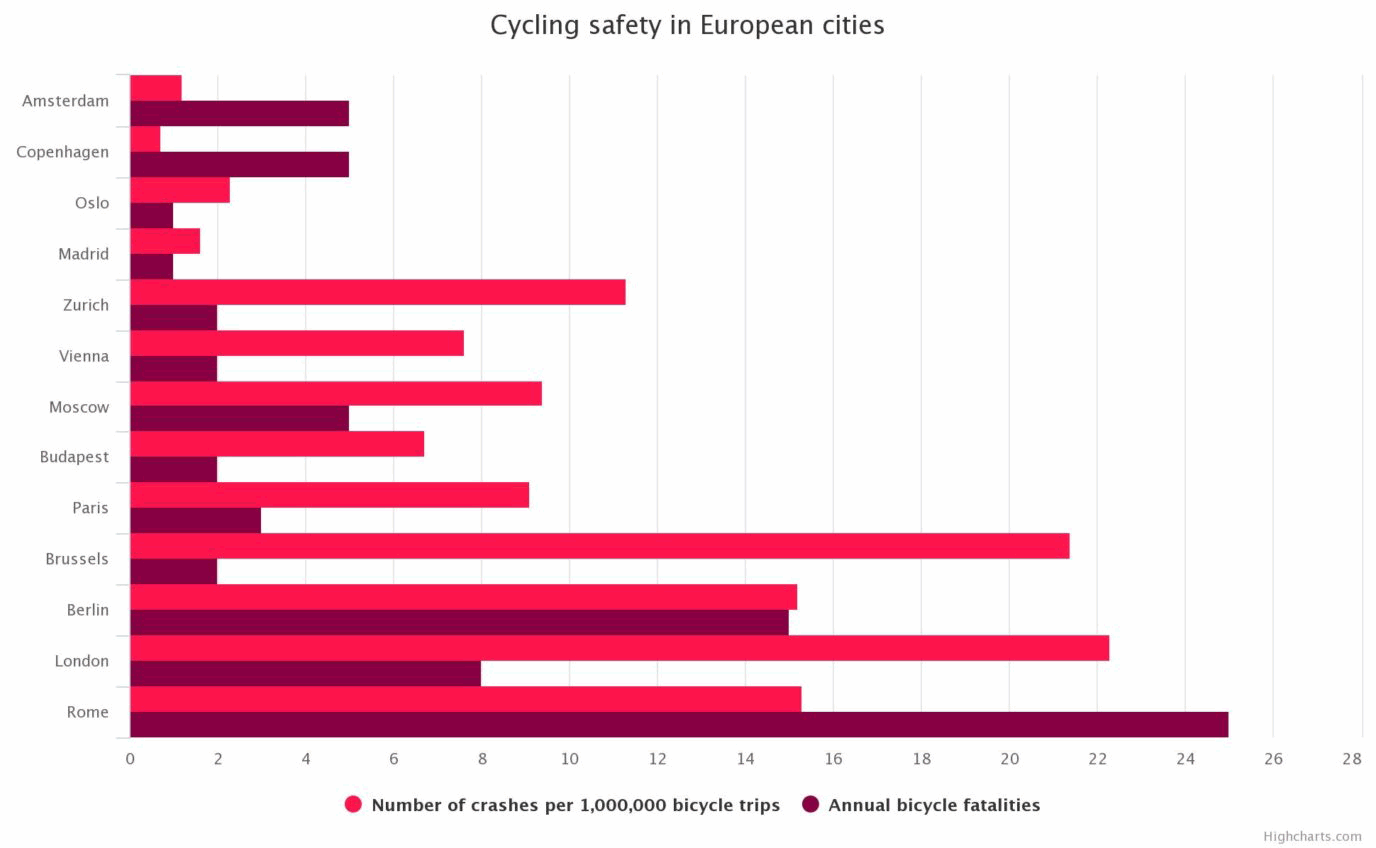

When compared with other European cities, the number of crashes per million trips is encouragingly low. [6].

We can now say that slow lanes were the origin of the so-called Modelo Madrid. The Madrid Model recognizes urban cycling as a transportation mode equal to any other, not requiring special infrastructure but granting the same rights to cyclists as to other vehicle operators. [7]

No cyclists ride on the sidewalk. Cyclists grant the same respect to pedestrians as they demand from motorists. Modelo Madrid puts in practice many of the principles pioneered by John Forester and refined in the United States by CyclingSavvy.

Modelo Madrid: the way of the future?

As with any other aspect of public policy, we can’t “ride” on our laurels — to paraphrase the English idiom — and expect equal treatment for cyclists in Madrid forever.

Economic stimulus money spent on “sustainable” projects is always a threat for urban cyclists, especially in these COVID-19 times. Going back to the segregated model is still possible. Some very loud cycling activists and associations are always demanding narrow bike lanes in the door zone or on sidewalks, following the North European model.

Here’s an example from Seville:

On the other hand, more Spanish cities are introducing slow lanes, especially after the COVID-19 lockdown: Valladolid, Burgos, Leganés, Granada…

Additional thoughts from Editor John Allen:

Which way should US states go? Could there be slow lanes on multi-lane streets in the USA? Keep in mind that higher speeds are common now on e-bikes, which probably did not in exist when Seville bikeways were planned and constructed.

Consider that automated crash avoidance is becoming common on motor vehicles, and improving. A transition to autonomous vehicles will follow, in time.

Suppose that a hoped-for decrease in motor traffic occurs with autonomous vehicles. Consider also the dangers of edge riding, and the reduction in efficiency and safety when turning vehicles must cross the path of through-traveling ones, rather than merging before turning.

All of these factors suggest that an integrated model like the Modelo Madrid could become more compelling as time passes.

Does US practice support the Modelo Madrid?

There is no specific mention in the model US traffic law [8] of different lanes with different posted speed limits. Yet these are in wide use, established indirectly.

In several states, large trucks are held to a lower speed limit than other vehicles [9], and are prohibited from using the leftmost lanes on multi-lane highways [10]. Edge-of-the road “friction” with parked vehicles, walk-outs, drive-outs and parking decreases the safe speed in the rightmost lane on city streets.

The general rule is to pass on the left, in the “fast lane”. But faster vehicles may pass bicyclists on the right in a right-turn lane, and sometimes a bus lane.

In all of these cases, the basic speed limit applies: to drive no faster than is reasonable and prudent. That speed is established by the design of the street and by the users who are present. Here’s an example of a bike lane to the left of a bus lane on University Avenue, Madison, Wisconsin. [11]

Footnotes

(Web links in the body of an article are more usual, but we prefer not to sidetrack readers into articles which need explanation, some in Spanish. So, these footnotes – Editor.)

[1] Newspaper article about the debt

[2] Newspaper article about the fine

[3] Online news article describing the original plan, with map

[4] City ordinance; translation of relevant sections into English

[5] Madrid Ciclista’s article “en Madrid no hay bicis” (“There are no bicycles in Madrid”) describes and promotes bicycle counts by citizens, and asserts that the city government has been undercounting.

[6] Crash rates in different European cities, and bicycle trends in Madrid. Article is in English: http://madridciclista.org/city-of-bikes/

[7] Madrid Ciclista article describing the Modelo Madrid.

[8] https://iamtraffic.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/UVC2000.pdf — see pages 147-148. Each US state enacts traffic law separately, and so there are differences.

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speed_limits_in_the_United_States

[10] https://static.tti.tamu.edu/tti.tamu.edu/documents/policy/congestion-mitigation/truck-lane-restrictions.pdf

[11] The University Avenue installation serves a large student population. The buses, on their fixed route, stay in the bus lane. More details here.