Where Bike Lane Design Collides with Savvy Cycling

If you’re an urban bicyclist, you probably know what “dooring” means. When bike lanes are entirely within reach of the doors of legally parked cars, it’s harder for bicyclists to ride safely.

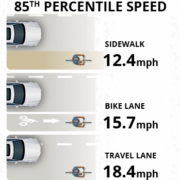

Even the cyclist who knows it’s not safe to ride in the door zone may feel that riding in the lane adjacent to an unusable bike lane is like riding with a flashing “Harass Me” sign.

Door-zone bike lane

Why do cities continue to make it hard to ride safely?

I address this issue in a new article in the journal Accident Analysis and Prevention. Door zone bike lanes (DZBLs) continue to be installed because design guidelines still allow them.

For decades, it has been conventional wisdom that crashes involving bicyclists and opening car doors are rare. This belief is based on motor vehicle crash reports, but these reports generally exclude this crash type by definition.

The crash hiding in plain sight

National and state databases only include crashes involving motor vehicles in transport. Since a parked car is not in transport, and a bicycle is not a motor vehicle, crashes where a bicyclist hits a parked car door are excluded.

A few dooring crashes make it into national and state crash databases anyway, which has led some studies to erroneously conclude that dooring accounts for less than 0.2 percent of bicycle crashes.

Dooring accounts for 12 to 27 percent of urban car-bike collisions, making it one of the most common crash types.

I found 10 sources in cities in North America, plus one from Australia, that include dooring incidents, unlike official crash data. These police, hospital, insurance or EMS reports indicate that dooring accounts for 12 to 27 percent of urban car-bike collisions, making it one of the most common crash types.

Substandard standards

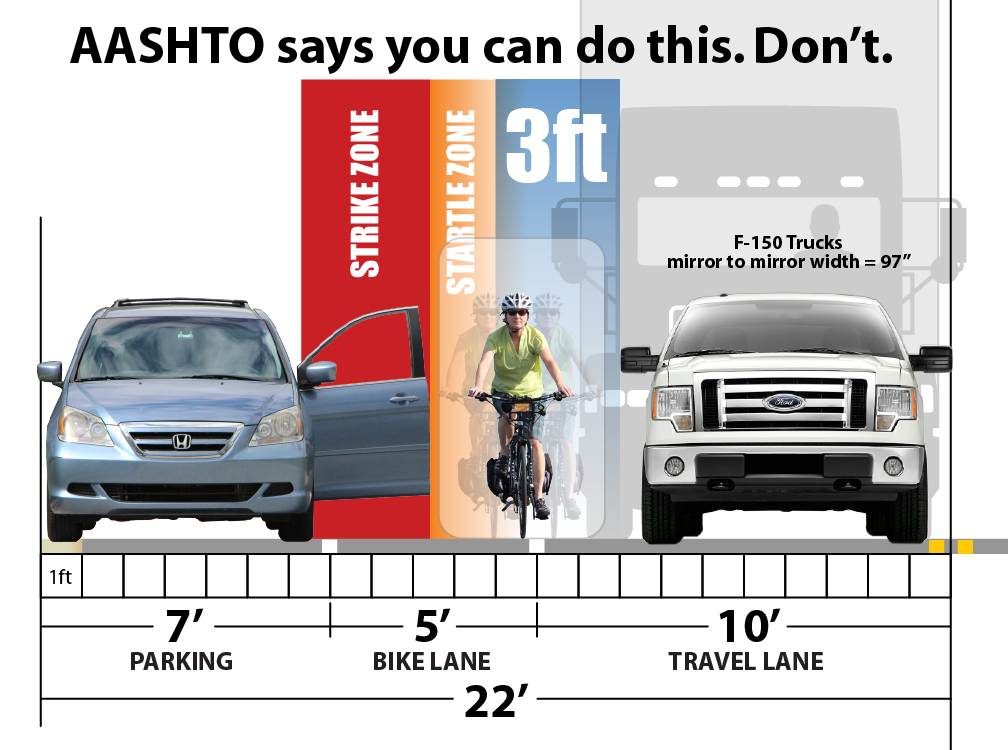

I reviewed four studies of bicyclist riding position with bike lanes and parking lanes of varying widths. With the minimum dimensions allowed (5-foot bike lane and 7-foot parking lane), almost all bicyclists were observed riding within reach of parked cars.

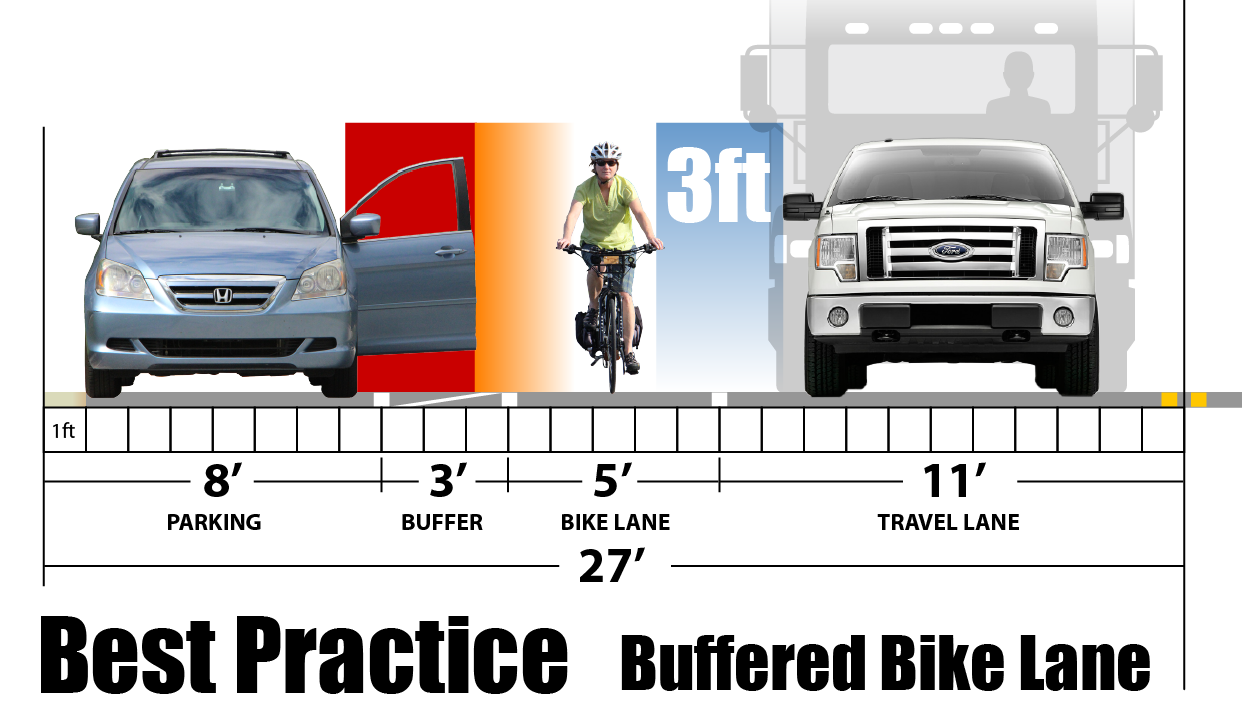

However, when there was another three feet between the bike lane and parked cars, almost all bicyclists rode outside the door zone.

When there was another three feet between the bike lane and parked cars, almost all cyclists rode outside the door zone.

Only one of the North American bike lane design manuals I could find (the Ontario Traffic Manual) requires a buffer between bike lanes and on-street parking. Paradoxically, the guidelines for separated bike lanes — where the bike lane is on the curb side of on-street parking — all require one.

Why require a buffer from car doors when the bike lane is on one side, but not when it’s on the other?

Designing to avoid dooring

In 2014, the Transportation Research Board published the results of a three-year, $300,000 study of bike lane width. The authors recognized that “the design of the bike lane should encourage bicyclists to ride outside of this door zone area and should account for the width of the bicyclist.”

The report found that bicyclists need to center themselves 12 feet from the curb to be outside of the door zone.

Change is slow, and stubborn

The Transportation Research Board’s report recognized best practices. Yet its authors still recommend installation of bike lanes that are less than 12 feet from the curb.

Even where there was enough room for a door buffer zone, the report recommended using half of the buffer zone on the travel lane side.

The authors are aware of the problem with their own recommendations. “Where bicycle lanes are designed according to the guidance [in this report], it should be recognized that bicyclists will still likely position themselves within the door zone of parked vehicles,” they wrote.

The researchers did not consider the possibility of recommending shared lane markings where there is insufficient room to install a bike lane outside the door zone, because their goal was to provide “design guidance for a bicycle lane given the decision that a bicycle lane will be installed.”

How bicyclists use shared lane markings

Some say that cyclists will ride in the door zone, even when not directed to by DZBLs. But is this really so?

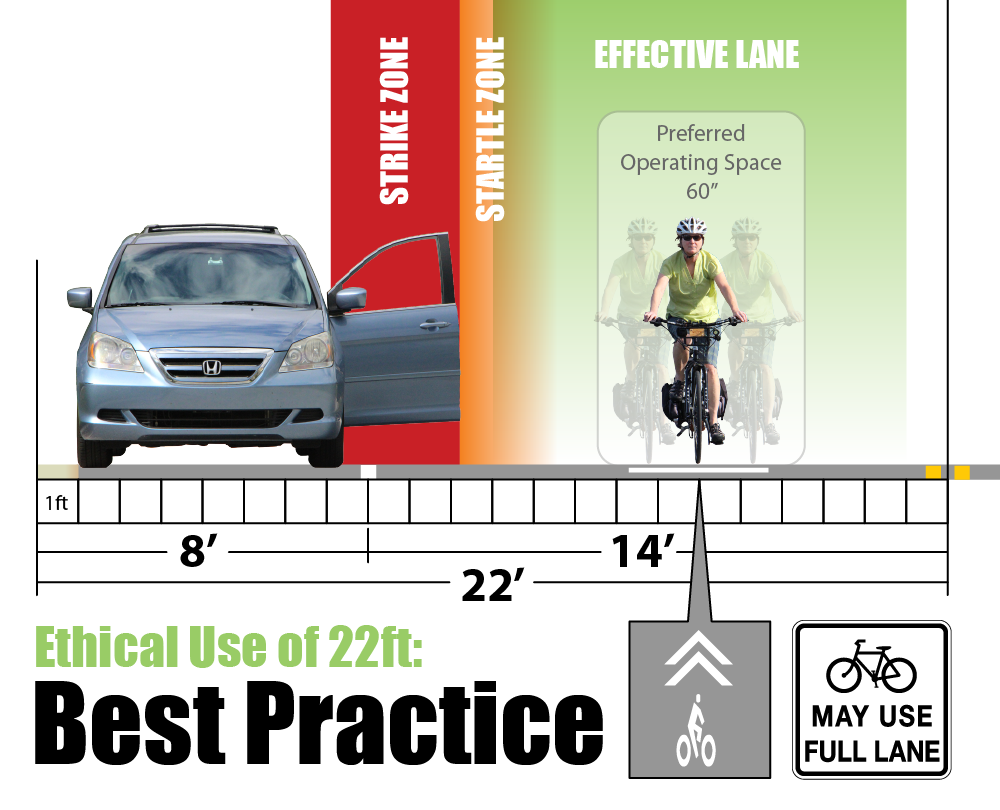

I looked at four studies that observed the position of bicyclists before and after shared lane markings were added in the center of a travel lane adjacent to on-street parking. The SLMs were centered about 14 feet from the curb; on average bicyclists were centered 11 feet from the curb.

In the most successful case, 85 percent of bicyclists were riding within the door zone before SLM installation, and only 45 percent after. In addition, there was a large drop in sidewalk bicycling. The posted speed limit was 25 MPH in this case, compared to 30-35 MPH in the others studied.

Shared lane markings can prevent dooring

Where there is on-street parking and insufficient room for a buffer from doors, SLMs can help keep cyclists out of the door zone. They could be more effective if supplemented by lower speed limits, eliminating statutes that require bicyclists to have an excuse to leave the right edge of the road, retraining police officers, and making the public aware of the right and need of bicyclists to keep a safe distance from parked cars.

Requiring a buffer for standard bike lanes will require design guides to acknowledge that bike lanes do not fit next to on-street parking without at least 3 feet more of width than is currently provided in the minimum guidance.

With less than 25 feet for a parking lane and travel lane, bicyclists should be encouraged to ride in the travel lane with shared lane markings and Bicyclists May Use Full Lane signs.

The future of door-zone bike lanes

The future of door-zone bike lanes

Currently the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities is being revised. However, unless the committee reviewing the current draft intervenes, DZBL designs will be retained. Although there will be new material on buffered bike lanes, the primary concern is a buffer between the travel lane and the bike lane, not on the parking side.

Accounting for the door zone properly would mean that bike lanes could not be installed with less than 25 feet between the curb and the center line.

There’s a pervasive belief, unsupported by evidence, that bicyclists using travel lanes are likely to be hit by overtaking motorists. Following this belief, the new AASHTO guide not only maintains designs that essentially require bicyclists to use the door zone, but also promotes designs requiring bicyclists to stay to the right of right-turning traffic.

Another pervasive belief is that bike lanes make bicycling easier. In fact, cyclists need more education to safely use bike lanes in urban contexts. The dooring risk is merely one of a host of issues with DZBLs.

How savvy cyclists protect themselves

If possible, find another route. If you find yourself on a road with a door-zone bike lane, you could use it with CyclingSavvy’s “control and release” strategy.

Because of traffic lights, motorists tend to travel in platoons. This leaves even busy roads empty for various stretches of time. When the regular travel lane is empty, use it, moving over as necessary to the door-zone bike lane to “release” other traffic.

When you move into any door-zone bike lane, slow down. Go slow enough so that a door opening in your path will not surprise you. For safety’s sake, this won’t be much faster than walking speed.

Be aware that while you’re in the bike lane, you’re not relevant to motorists. Beware of drivers who may turn right in front of you, or left across your path. A door-zone bike lane also shields you from motorists who may be driving onto the road at an intersection or from a driveway.

Never use a door-zone bike lane as a “freeway” to speed by motor traffic stopped and stuck on your left. In these situations, filter forward cautiously (no faster than pedestrian speed).

If door-zone bike lane designs proliferate, savvy cyclists will increasingly have to take longer routes in order to avoid the possibility of harassment (or citation, in cities and states with mandatory use laws for bike lanes). The door zone is a real hazard that must be accounted for in designing for safe bicycling.

Paul, thanks so much for writing up this summary of your important research. Along with Keri’s illustrations this is a very informative post that all cyclists should read. And if we’re lucky, maybe it will have some positive influence on the next version of the AASHTO guidelines for bike lanes.

Excellent, Paul!

Dooring wouldn’t even be a problem at all if people looked before throwing their door open.

Loubrio, there is zero chance that you or I can change that behavior.

But we can tell bicyclists to not ride in the door zone.

I disagree. Educating occupants of cars to use the Dutch Reach works. Virtually everyone in the Netherlands uses the DR. Check out http://www.dutchreach.org.

Great stuff Paul! I also LOVE the new gauntlet illustration (thanks Keri, I believe). This article and the illustrations make the DZBL issue very clear and easy to understand!

Thanks

I am not qualified to question the numbers about DZBL accidents but I’m flabbergasted by the a couple sentences near the end.

First “When you move into any door-zone bike lane, slow down. Go slow enough so that a door opening in your path will not surprise you. For safety’s sake, this won’t be much faster than walking speed.” really? You or your organization recommends walking speed bicycle riding in a bike lane? Was this included for liability reasons? I find it absurd that anyone would recommend riding a bike at walking speed in a bike lane. Even on my most slow pokey days, sitting upright on the xtra-cycle, I’m doing 8-9 mph which is roughy 3x as fast as pedestrian speed. I’d say that for most cyclists, riding a bicycle at 3 mph is unsafe. (average walking speed of 3.1mph from reference.com)

I would think that something called Cycling Savvy would give instruction on scanning cars for heads, or looking in side view mirrors for faces or looking for illuminated brake lights on cars as one cycles. At various times, I use these techniques to cruise the streets of Davis.

Second, “Be aware that while you’re in the bike lane, you’re not relevant to motorists. ” Besides the moral argument that it’s not OK to mow down humans who happen to be cycling, I live in California and the California Vehicle code would seemingly disagree with this statement. Motorists are responsible for the safe operation of their vehicles. For example, CVC 22107. No person shall turn a vehicle from a direct course or move right or left upon a roadway until such movement can be made with reasonable safety….

It is kind of weird that the simplest things can be the hardest to find in the CVC. But also in general, you’re not allowed to drive or ride willy nilly anyway you like.

John, in 1967, headrests became mandatory in cars. A couple decades after that, tinted glass became nearly universal. For those reasons, looking in a car to see if there are occupants hasn’t even been possible.

And it has never been a good idea. There is too much else in the roadway environment that you should be scanning for.

I agree with you that 3 mph is too slow. My rule of thumb is that most bicyclists need to be going 7 mph or faster to be reasonably stable. Watching cyclists wobble during starting and stopping, when they have to transition from zero to cruising speed, reinforces my belief in that.

If you do a time-speed-distance calculation, you realize the absurdity of trying to tell cyclists to be ready to react when a car door opens. Begin with a cruising speed of 11 feet per second at 7.5 mph. Now add the traffic engineer’s commonly accepted 2.5 second reaction time. (I know that sounds slow, but that number was not casually arrived at.) Now add braking distance, knowing that an 85th percentile (that means good) bicyclist can only muster 0.3 Gs of braking deceleration. Or, if you choose to not brake, consider the time required to look, signal and merge left. Whoops, what if traffic prevents you from merging left? What’s your Plan B?

Regarding “not relevant to motorists,” don’t confuse legality with perceptual psychology. Motorists watch where they are going. Many an experiment has confirmed what I observe when I drive my own car: We look at the lane ahead, and ignore the rest. A bicyclist in a bike lane is “the rest,” which is why the phrase “not relevant” gets used.

Bike lane proponents have spent 50 years pretending that dooring collisions aren’t a serious problem. In so doing, they have killed many of their customers, injured many thousands, and created the perception that bicycling has this huge inherent risk that can’t be changed.

Oh, but this risk can be eliminated! Just eschew the door zone, regardless of how they’ve tarted it up with a paint brush!

That’s why Cycling Savvy says “control the travel lane.”

Agreed, John and John!

It’s best to use Paul’s first suggestion: Find another route (one that doesn’t have a door-zone bike lane).

When that’s not ideal, I’ve had great success with the “control and release” strategy.

Hi John (Hess),

I’ve lived in California all my life and was a cop, including bike cop, for almost 24 years. I still teach bike patrol to officers and beyond.

Unfortunately as we all know, ALL roadway users at some point violate traffic laws (willfully or not) and sometimes collisions occur as a result. The “gauntlet” illustration clearly shows the common motorists’ mistakes leading to conflicts and possible collisions between motorists and cyclists! The GOOD NEWS is we as bicyclists can help ourselves and motorists by eliminating and/or greatly reducing these conflicts in the first point!

Riding (driving your bike) away from these common conflicts and hazards IS safe, legal, relevant, cooperative and the BEST and less stressful practice! Of course, this means normally controlling the lane.

As an example for us is California, you can find the sections that allow cyclists to control the traffic lane under CVC 21202 (FTR, Far to Right) and 21208 (Bike Lane). The important parts of these sections are the EXCEPTIONS to the general laws.

I would also like to say for cyclists fearing by controlling the lane will lead to being rear ended by a motor vehicle is very rare. Buzzes and side sweeps are much more common for the FTR cyclist.

Hope this helps!

People have to take a look in the mirror before they are standing out of the car.