Worcester Turnpike to Route 9 to…?

We can’t understand our present time — or plan for the future — unless we know how we got here. In a previous post, I described how I ride on Massachusetts Route 9. Now I’ll tell you what that makes me think about. Bear with me.

Backstory

One of the pleasures of riding in eastern Massachusetts is to discern the age and the history of roads from their meanderings, and by studying the buildings along them. Most rural roads here pre-date the advent of motor vehicles. That works well for bicyclists. Roads follow the contours of the land, except for notorious roads with “hill” in their name,

From the arrival of the first humans as glaciers retreated, until the arrival of settlers from Europe in the 1600s, there was only singletrack, trodden on foot.

Settlers introduced horses, oxen and wagons. Many old trails widened to doubletrack. The settlers located early town centers on hilltops for defense against Native Americans who did not like being driven from their lands. Settlers later built town centers in valleys with water power for mills. Local people would organize a “bee” — a day when they’d get together for road maintenance. Distances between towns were short, so farmers could manage a day trip by wagon to market and back.

I can infer all this as I ride my bicycle in the Eastern Massachusetts countryside. Some old roads still have stone mile markers from before the Revolution.

In the 1700s, Benjamin Franklin organized the postal service. Town-to-town roads, strung together, connected major population centers. Parts of U.S. Route 20, which passes a half mile from my home, are still called the Boston Post Road. It connected to New York and beyond.

From the Worcester Turnpike to Route 9

In the early 1800s, private companies established turnpikes with government authorization. These toll roads radiated out in several directions from Boston. The Worcester Turnpike heads west to — Worcester. The Turnpike was created in one political stroke, rather than its evolving like most roads. For this reason, it is quite straight, and for the most part, avoids town centers.

A turnpike toll house and toll gate, early 1800s — from robertpeecher.com

Turnpikes served budding intercity commerce, but they soon failed financially. They were expensive to construct. Unlike modern toll roads, the turnpikes had no access control. “Shunpikes” went around the tollgates.

By the mid-1800s, railroads linked cities. The turnpikes couldn’t compete. Many did continue to exist, under government management and free for users.

The eastern half of the Worcester Turnpike survived; the western half deteriorated. In 1903, the entire Worcester Turnpike revived, hosting a light rail line. Trolley cars stopped running in 1932 as increasing use of motor vehicles drained demand. Some political shenanigans occurred, too, as Joe Orfant, expert on Route 9, has told me. He has written a fascinating detailed history.

“The Finest Motor Road in the World”

You’ve probably read about struggles to improve roads toward the end of the 1800s, involving in no small part bicyclists and the bicycle industry. But hardly any roads outside urban areas were paved before the 1920s.

In 1933, benefiting from Depression stimulus funding, the Worcester Turnpike was designated as a segment of Massachusetts Route 9, and extensively rebuilt. At the time of this construction it was heralded as “the finest motor road in the world.” It relieved the congestion on Route 20, which meandered through town centers.

Route 9’s two roadways separated by a median identify it as a precursor of the German Autobahns and New York-area parkways, constructed in the mid- to late 1930s; the Pennsylvania Turnpike (1942); and limited-access highways everywhere.

Route 9, Southborough, Massachusetts. Same location, 2011.

A Transitional Design

Even though much of Route 9 seems interstate-like today, designation of the Worcester Turnpike segment as a limited-access highway has never been possible.

Today’s transportation engineers would not create this sort of roadway through a densely populated area. But by necessity Route 9 is “grandfathered,” because it is lined with businesses and residences. and offers the only access to numerous side streets.

Reaching most destinations on the opposite side requires continuing to the next interchange and doubling back. Space-saving interchanges require drivers to slow before exiting and stop for through traffic before entering. Many of these interchanges still exist, largely unchanged.

Massachusetts Route 9 and Bicyclists

The Worcester Turnpike segment of Massachusetts Route 9 is not quiet or pleasant for bicycling. Until recent years, though, it has been serviceable for bicyclists of an average adult skill level. Route 9’s wide shoulders are easy riding. Its slow-and-stop intersections are tame.

But parts of Route 9 have been modified, one by one, to accommodate increases in motor traffic. From early on, many minor cross streets were interrupted. This works well for bicyclists who don’t need to cross the highway, and poorly for those who do.

And when the Massachusetts Highway Department builds or reconstructs an interchange with a limited-access highway, it tends to add limited-access highway features to the intersecting road. Such it the case with the Route 95 interchange.

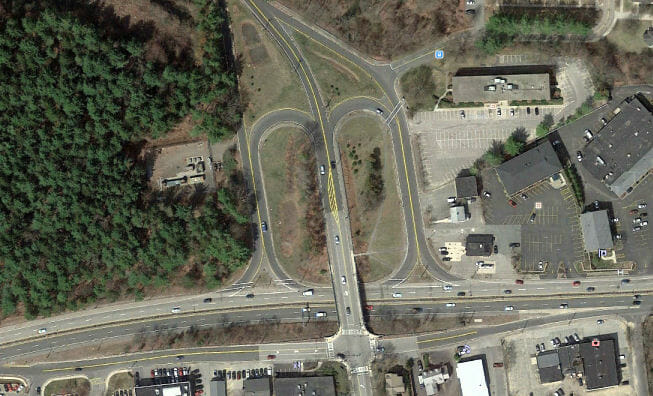

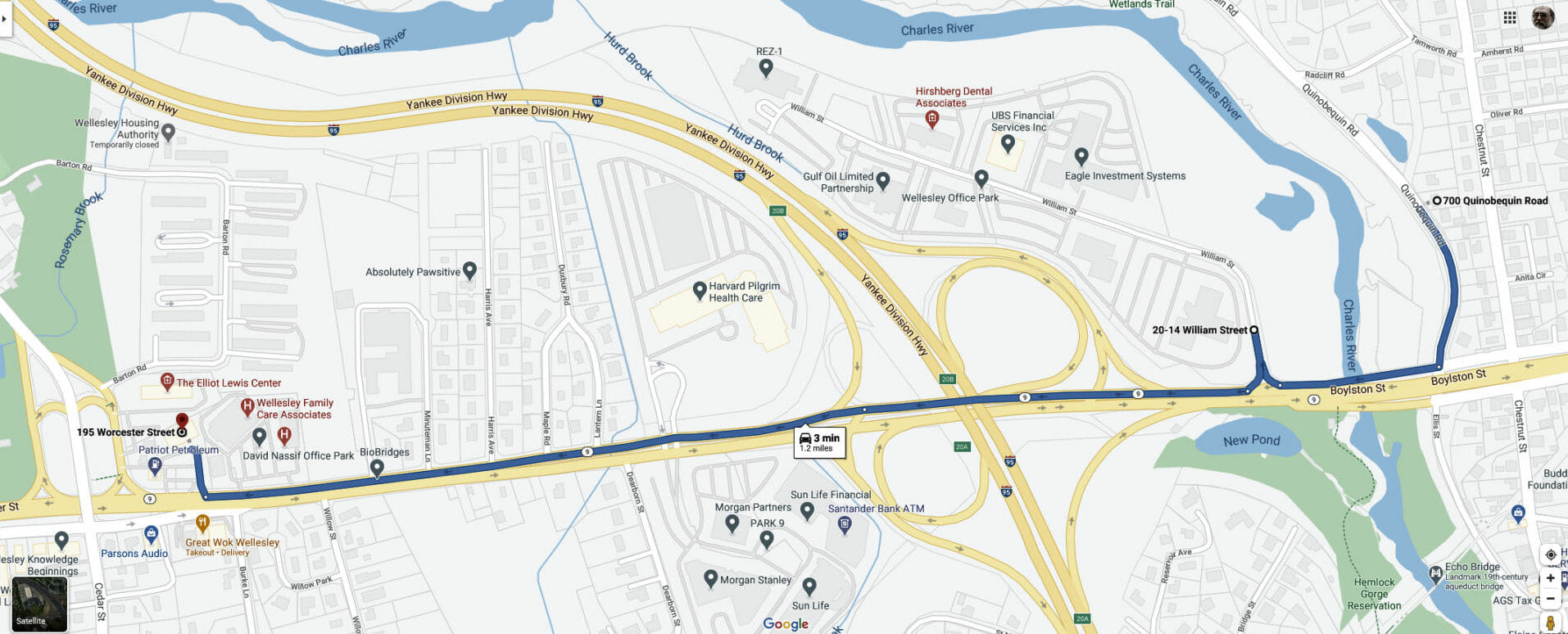

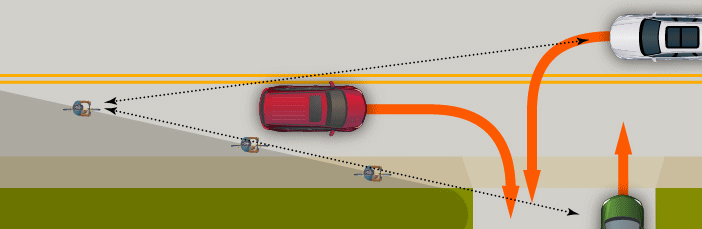

From the time of its construction in the early 1950s until recent years, the interchange with Interstate 95 was a full cloverleaf, as shown in the satellite image above. Route 9 had two weave areas where traffic slowing for an off ramp crossed traffic accelerating from an on ramp. These weaves were underneath the Route 95 overpass.

Traffic slowing down mixing with traffic speeding up inside an underpass on a high-speed highway is not a great concept.

Redesign of the Route 9/I-95 Interchange

Revised design in the mid-2010s eliminated the weaves, introducing instead a couple of signal-controlled left turns. This “partial cloverleaf” design includes reduced vegetation, which improves sight distances.

What does all this mean for bicyclists?

I’ve already described the specifics of a trip which required me to ride through the interchange. Granted, the present configuration is better than the earlier full cloverleaf. As I showed in my previous post, I was able to negotiate it using lane control and a CyclingSavvy bag of tricks.

Bicyclists could use sidewalks. These meet the letter of the law for the Americans with Disabilities Act, though not exactly the spirit of the law. How would you like to negotiate a wheelchair crammed in next to high-speed travel lanes through an underpass? In winter, sidewalk users often must clamber over mounds of plowed snow. Distances are long for walking.

Opportunity is Possible in an Auto-Centric Landscape

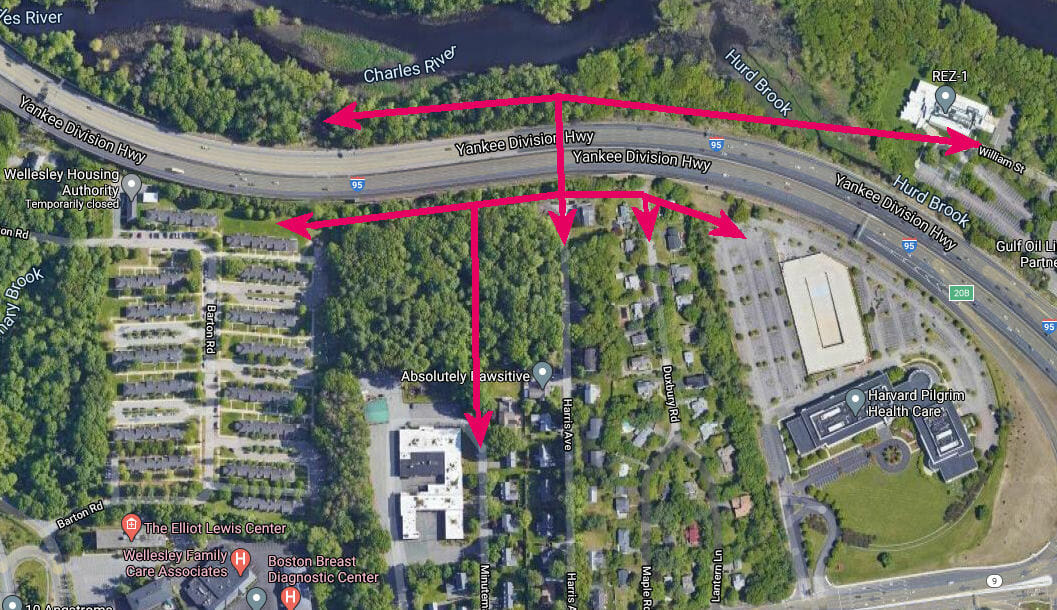

In an ideal world, pedestrians and slower, local, wheeled traffic — people on foot, bicycles, e-bikes — would not to have to use Route 9 at all. But this traffic would have to cross Route 95 somewhere.

Including a separate underpass or overpass while reconstructing the interchange would have added little extra cost to the project. It didn’t happen, no thanks to the Massachusetts Department of Transportation Highway Division.

But a single overpass and less than a mile of paths could connect the William Street office park, east of Route 95, to Cedar Street and several residential streets to the west, also opening up a riverfront park to residents and to workers. Route 95 crosses the Charles River on a bridge north of the interchange. A path on a boardwalk could run next to the river. Just sayin’.

Worcester Turnpike, to Route 9, to the Big Picture

My story raises the larger question of sustainability of the transportation system and world economy. The die was cast in the mid-1800s as railroads bootstrapped the accessibility of coal — fossil fuel — for themselves, for industry, and for space heating, supplanting water power and wood.

Then petroleum made possible the motor vehicles which led to demand for motor roads. These among other technological developments allowed the world to support an increasing human population.

It’s easy to look at what succeeds in the present while neglecting thoughts for the future. It should have been obvious from the start that fossil fuel resources were finite. Grimly, climate change — caused by fossil fuel use — is catching up with us faster.

I almost regret saying this, but the present Covid-19 pandemic is showing us how bicycling becomes more popular in times of crisis. No matter how the future unfolds, people will ride bicycles. The more difficult conditions get, the more people will need them. For all of us, this is motivation to make bicycling better.